Article

Patients with undiagnosed bleeding disorders can present with varying clinical features ranging from innocuous bruising to life-threatening haemorrhage. Haemophilia is an X-linked recessive bleeding disorder causing a disruption within the intrinsic clotting pathway. After trauma, patients with Haemophilia experience an increased bleeding time with excessive bleeding into mucosal tissue, muscles and joints,1 which carries a significant risk of morbidity and mortality.2 The authors highlight the diagnostic and management actions undertaken for a paediatric patient, in whom Haemophilia A was an incidental finding, who suffered a craniofacial injury.

An 18-month-old child presented with his parents to the Emergency Department following a mechanical fall with a persistent and expanding forehead swelling. Clinically, a 5 x 4 cm firm swelling over the left frontal region was noted (Figure 1). There was no family history of bleeding disorders.

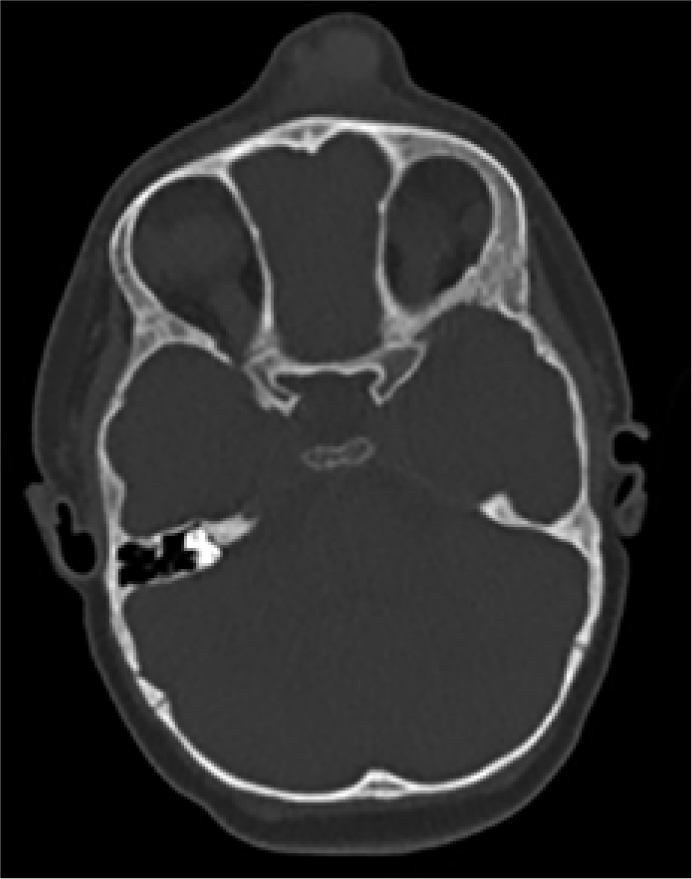

An urgent CT head was requested to rule out intracranial haemorrhage and fractures, which returned as normal (Figure 2). Haematological investigations revealed a factor VIII deficiency (< 0.01) indicating severe Haemophilia A. The haematoma was surgically drained under a general anaesthetic and the patient referred to a tertiary haematology centre for ongoing management.

The severity of Haemophilia is dependent upon the levels of remaining factor VIII and < 1% of the population suffer with severe Haemophilia. The usual presentation time for Haemophilia is during infancy after a traumatic event,3 as noted in this case. Emphasis should be placed upon obtaining a comprehensive history, examination and focused haematological investigations.4 Undiagnosed paediatric cases of Haemophilia A can present to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery department with abnormal bleeding following trauma. This stresses the importance of screening appropriate patients to diagnose this lifelong bleeding disorder5 and liaising with haematologists as necessary.

This case highlights the need for clinical vigilance in a child presenting with an inconsistent injury pattern following a perceived trivial injury. Optimum lifelong management of this patient was ensured.