Article

Specialist referral may be indicated if the Practitioner feels:

Oral cancer

Oral cancer is the most common malignant epithelial neoplasm affecting the mouth. More than 90% is oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) (Table 1).

|

|

Oral squamous cell carcinoma

Cancers of the oral cavity are classified according to site:

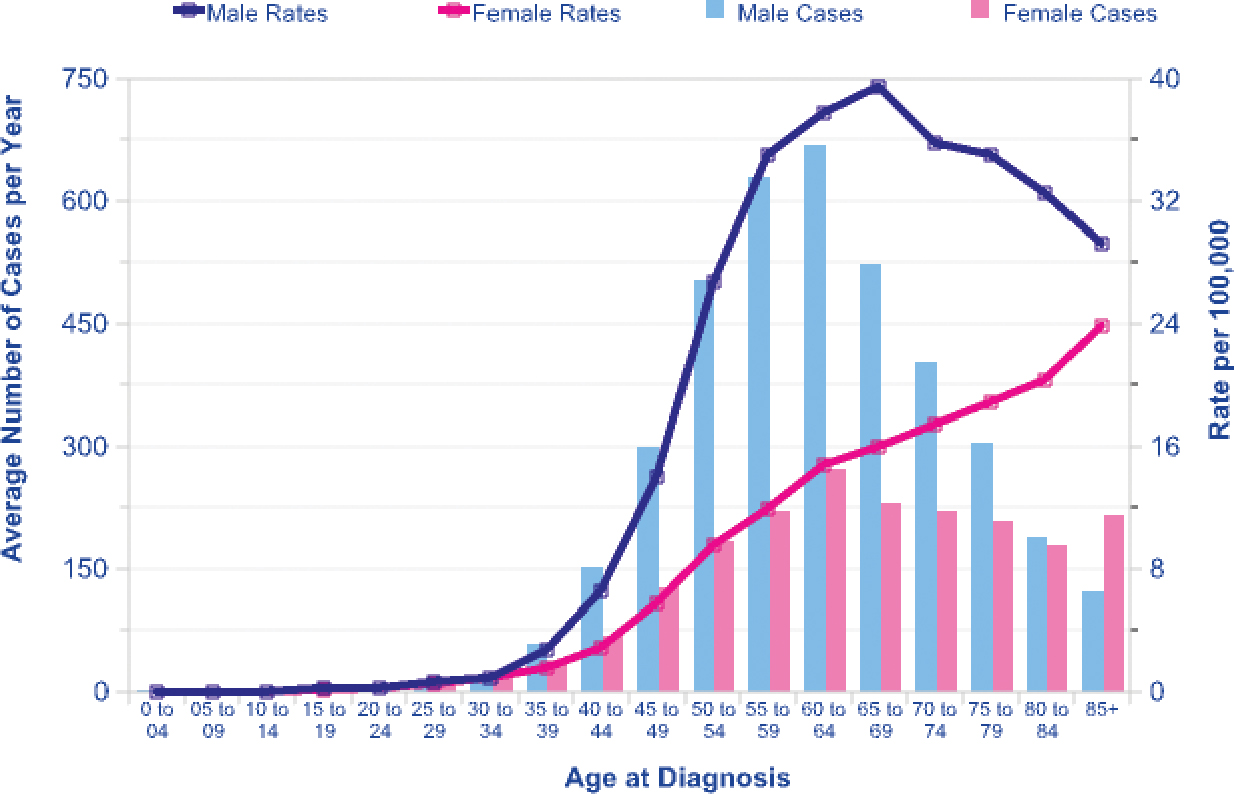

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is among the ten most common cancers worldwide and seems to be increasing. The number of new mouth (oral) and oropharyngeal cancers are currently estimated to be 300,000 cases world-wide, amounting to around 3% of total cancers. The mortality rate is just over 50%, despite treatment. In the UK, the total number of recorded cases of oral cancer is around 5400 per annum (Figure 1), with around 1700 deaths mainly due to late detection. The incidence appears to be rising in the UK and many other countries. In the UK, there was a 17% increase in cases of oral cancer from 3,673 (1995) to 4,304 (1999). Scotland has about double the incidence rate of oral cancer compared with England.

OSCC is seen predominantly in males but the male: female differential is decreasing. OSCC is seen predominantly in the elderly but is increasing in younger adults.

Potentially malignant states

Some potentially malignant (precancerous) lesions which can progress to OSCC include especially (Table 2):

| Lesion | Aetiology | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Erythroplasia | Tobacco/alcohol | Flat velvet, red plaque |

| Leukoplakia | Tobacco/alcohol | White or speckled plaque |

| Actinic cheilitis | Sunlight | White plaque/erosions |

| Lichen planus | Idiopathic | White plaque/erosions |

| Submucous fibrosis | Areca nut | Immobile mucosa; fibrous bands; mucosal pallor |

| Discoid lupus erythematosus | Idiopathic | White plaque/erosions |

| Chronic candidosis | Candidal infection (most commonly Candida albicans) | White or speckled plaque most commonly on the buccal mucosa at the commissure |

| Syphilitic leukoplakia | Syphilis | White plaque |

| Paterson-Kelly syndrome (sideropenic dysphagia; Plummer-Vinson syndrome) | Iron deficiency | Post-cricoid web |

| Dyskeratosis congenita | Genetic | White plaques |

Some other potentially malignant (precancerous) conditions include:

Predisposing factors (risk factors)

OSCC is most common in older males, in lower socioeconomic groups and in ethnic minority groups.

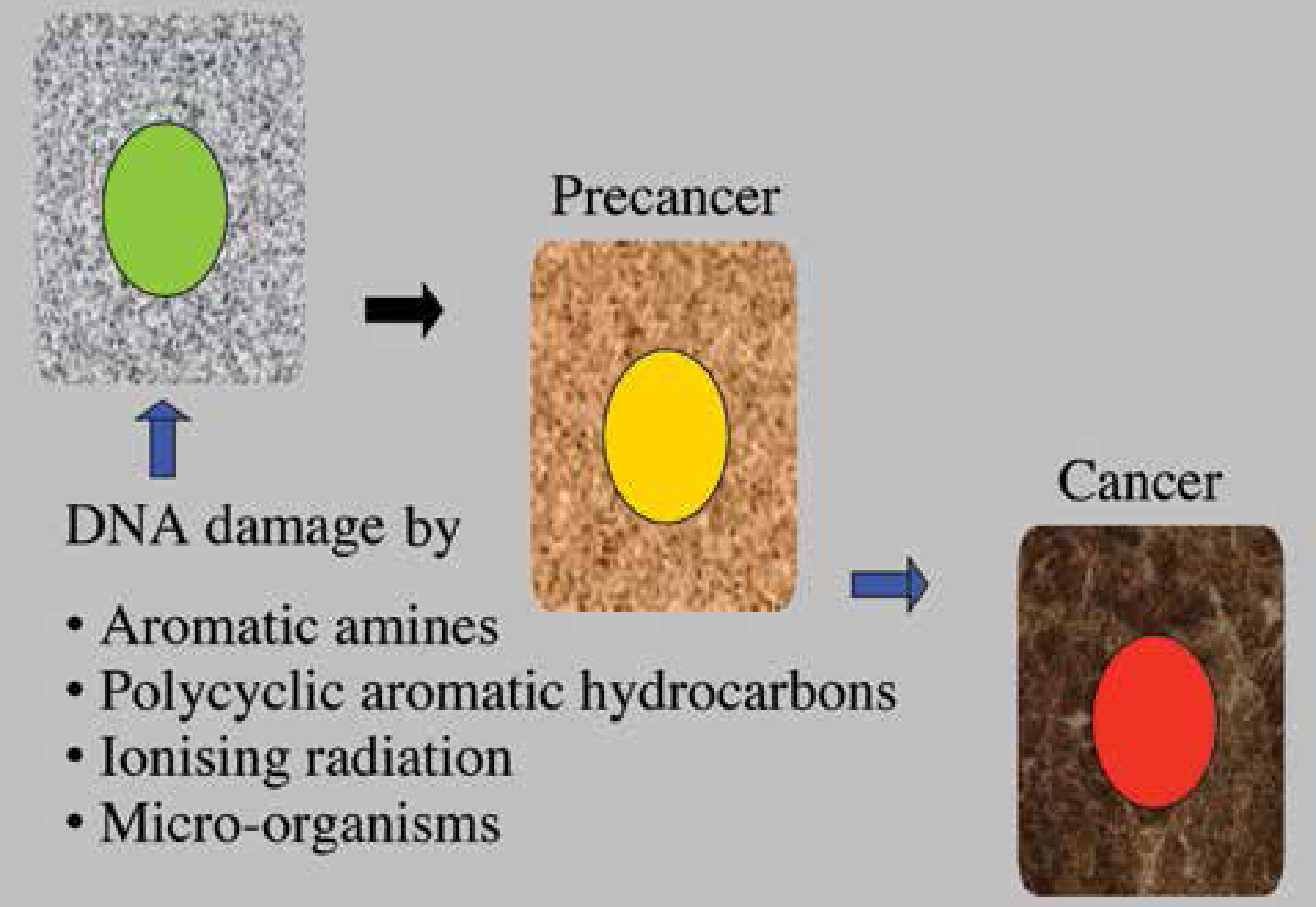

OSCC arises because of damage to DNA (mutations) which can arise spontaneously, probably because of free radical damage, or can be caused by chemical mutagens (carcinogens), ionizing radiation or micro-organisms. OSCC arises as a consequence of multiple molecular events causing genetic damage affecting many chromosomes and genes, and leading to DNA changes. The accumulation of genetic changes leads to cell dysregulation to the extent that growth becomes autonomous and invasive mechanisms develop – this is carcinoma (Figure 2).

Intra-oral SCC is seen especially in relation to various lifestyle habits. These are mainly tobacco and alcohol related. Tobacco, whether smoked or chewed, releases a complex mixture of at least 50 compounds, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as benzpyrene, nitrosamines, aldehydes and aromatic amines which are carcinogens. There is some evidence to suggest that second-hand smoke may increase oral cancer. Pipe smoking was previously associated with lip cancer. However, pipe smoking has decreased in popularity and may help explain the reduced incidence of lip cancer. The risk of oral cancer related to tobacco exposure is both duration- and dose-dependent. Smoking cessation leads to a reduction in the risk but it may take 20 years before the risk is similar to that seen in lifelong non-smokers.

Alcohol (ethanol) is metabolized to acetaldehyde, which may be carcinogenic. Nitrosamine and urethane contaminants may also be found in some alcoholic drinks. Alcohol damage to the liver might, by impairing carcinogen metabolism, also play a role.

The combination of tobacco use and alcohol consumption is particularly implicated in OSCC. People who both smoke and drink alcohol have a significantly greater risk of oral cancer than those who only smoke or drink alcohol.

Betel quid often contains betel vine leaf, betel (areca) nut, catechu, and slaked lime which, together with tobacco, appears to be carcinogenic. Some 20% of the world's population use betel. In people from the developing world, OSCC is seen especially in tobacco or alcohol users and particularly in betel quid users. Various other chewing habits, usually containing tobacco, are used in different cultures (eg Khat [Qat], Shammah, Toombak).

Other factors

All tobacco/alcohol users do not develop cancer, and similarly not all patients with cancer have these habits, and thus other factors must also play a part.

These may include:

Clinical features

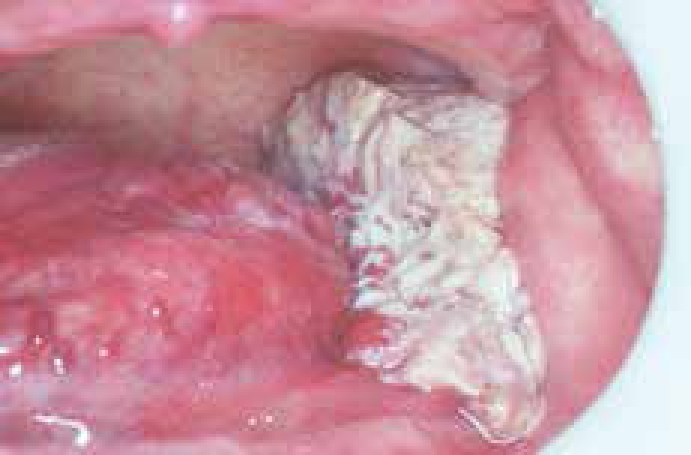

Most oral cancer is carcinoma on the lower lip where it may be preceded by, or associated with, actinic cheilitis (Figure 3) induced by chronic exposure to sunlight, and typically presents as a swelling or lump (Figure 4); the other main site is intra-orally, especially on the postero-lateral border/ventrum of the tongue (Figure 5).

Intra-oral OSCC may present as an indurated lump/ulcer, ie a firm infiltration beneath the mucosa (Figures 6 and 7); a lump sometimes with abnormal supplying blood vessels; a red lesion (erythroplasia); a granular ulcer with fissuring or raised exophytic margins; a white or mixed white and red lesion (Figure 8); a white lesion (Figure 9), a non-healing extraction socket; a lesion fixed to deeper tissues or to overlying skin or mucosa; or cervical lymph node enlargement, especially if there is hardness in a lymph node or fixation. OSCC should be considered where any of these features persist for more than 3 weeks (Figure 10).

It is important to note that in patients with OSCC, a second primary neoplasm may be seen elsewhere in the upper aerodigestive tract in up to 25% over 3 years. Indeed, many patients treated for OSCC succumb to a second primary tumour rather than a recurrence of the original tumour.

Diagnosis

Management of early cancers appears to confer survival advantage and is also associated with less morbidity and needs less mutilating surgery. Thus it is important to be suspicious of oral lesions – particularly in patients at high risk, such as older males with habits such as the use of tobacco, alcohol or betel. There should thus be a high index of suspicion, especially of a solitary lesion. Clinicians should be aware that single ulcers, lumps, red patches, or white patches – particularly if any of these are persisting for more than 3 weeks, may be manifestations of malignancy.

Frank tumours should be inspected and palpated to determine extent of spread; for tumours in the posterior tongue, examination under general anaesthesia by a Specialist may facilitate this.

The whole oral mucosa should be examined as there may be widespread dysplastic mucosa (‘field change’) or even a second neoplasm and the cervical lymph nodes and rest of the upper aerodigestive tract (mouth, nares, pharynx, larynx, oesophagus) must be examined.

Investigations

It is essential to determine whether bone or muscles are involved or if metastases–initially to regional lymph nodes and later to liver, bone and brain – are present. Imaging may be needed (Figures 11 and 12). Another important aspect in planning treatment is to determine if there is malignant disease elsewhere, particularly whether other primary tumours are present, and therefore endoscopy may form part of the initial assessment.

Urgent referral should be made but, if a Specialist opinion is not readily accessible, an incisional biopsy can be done in general practice if the practitioner is both competent and confident to carry this out. If you ARE concerned, phone, e-mail or write for an URGENT Specialist opinion, which is indicated if you feel a diagnosis of cancer is seriously possible or if the diagnosis is unclear. One of the most difficult clinical situations in which clinicians find themselves is with the patient in whom cancer is suspected. Patient communication and information are important. If the patient is to be referred to a Specialist for a diagnosis and insists (rightly) on a full explanation as to why there is a need for a second opinion, it is probably better to say that you are trained more to be suspicious but hope the lesion is nothing to worry about, though you would be failing in your duty if you did not ask for a second opinion. However, you should leave discussion of actual diagnosis, treatment and prognosis to the Specialist concerned, as only he/she is in a position to give accurate facts regarding future management to the patient concerned.

The biopsy should be sufficiently large to include enough suspect tissue to give the pathologist a chance to make a diagnosis and not to have to request a further specimen. Since red rather than white areas are most likely to show dysplasia, a biopsy should be taken of the former. Some authorities always take several biopsies at the first visit in order to avoid the delay and aggravation resulting from a negative pathology report in a patient who is strongly suspected as suffering from a malignant neoplasm. Attempts to highlight clinically probably dysplastic areas before biopsy, eg by the use of toluidine blue dye and other vital stains, may be of some help where there is widespread ‘field change’. Molecular techniques are being introduced for prognostication in potentially malignant lesions and tumours, and to identify nodal metastases.

Finally, the Specialist also needs to ensure that the patient is as prepared as possible for the major surgery required, particularly in terms of general anaesthesia, potential blood loss and ability to metabolize drugs, and to address any potential medical, dental or oral problems pre-operatively, to avoid complications.

Therefore, almost invariably, the following are indicated:

Selected patients may also need:

Management

Cancer treatment involves a team approach including a range of specialties involving surgeons, anaesthetists, oncologists, nursing staff, dental staff, nutritionists, speech therapists and physiotherapists, and others. Increasingly, Head and Neck Tumour Boards are being developed along with Cancer Networks to facilitate the collaboration of providers of cancer services to provide seamless care based on best practice. Consensus guidelines to treatment are now being published.

OSCC is now treated largely by surgery and/or radiotherapy to control the primary tumour and metastases in cervical lymph nodes. Treatment and prognosis depend on the TNM classification (Tables 3 and 4).

| Primary tumour size (T) | |

| Tx | No available information |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumour |

| Tis | Only carcinoma in situ |

| T1, T2, T3, T4 | Increasing size of tumour. T1 maximum diameter of 2cm; T2 maximum diameter of 4cm; T3 maximum diameter over 4cm. T4 massive tumour greater than 4cm diameter, with involvement of antrum, pterygoid muscles, base of tongue or skin |

| Regional lymph node involvement (N) | |

| Nx | Nodes could not be or were not assessed |

| N0 | No clinically positive nodes |

| N1 | Single clinically positive ipsilateral node less than 3cm in diameter |

| N2 | Single clinically positive ipsilateral node 3cm to 6cm in diameter, or multiple clinically positive homolateral nodes, none more than 6cm in diameter |

| N2a | Single clinically positive ipsilateral node 3cm to 6cm in diameter |

| N2b | Multiple clinically positive ipsilateral nodes, none more than 6cm in diameter |

| N3 | Massive ipsilateral node(s), bilateral nodes, or contralateral node(s) |

| N3a | Clinically positive ipsilateral node(s), one more than 6cm in diameter |

| N3b | Bilateral clinically positive nodes |

| N3c | Contralateral clinically positive node(s) |

| Involvement by distant metastases(M) | |

| Mx | Distant metastasis was not assessed |

| M0 | No evidence of distant metastasis |

| M1, M2, M3 | Distant metastasis is present. Increasing degrees of metastatic involvement, including distant nodes |

| Stage | TNM | Approximate % survival at 5 years |

|---|---|---|

| I | T1 N0 M0 | 85 |

| II | T2 N0 M0 | 65 |

| III | T3 N0 M0 |

40 |

| IV | Any T4, N2, N3 or M1 | 10 |

The planning phase includes discussions regarding restorative and surgical interventions required before cancer treatment, including osseo-integrated implants and jaw and occlusal reconstruction, and therapy is also planned to avoid post-operative complications. As much oral care as possible should be completed before starting cancer treatment.

Oral care is especially important when radiotherapy is to be given, since there is a liability particularly to mucositis, xerostomia and other complications, and a risk of osteonecrosis – the initiating factor for which is often trauma, such as tooth extraction, or ulceration from an appliance, or oral infection.

Websites and patient information

http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/mouth-cancer/DS01089

http://www.oncolink.org

http://www.oralcancer.org

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/oralcancer.html

http://www.dh.gov.uk/PolicyAndGuidance/HealthAndSocialCareTopics/Cancer/fs/en

http://www.rdoc.org.uk/