Article

Specialist referral may be indicated if the Practitioner feels:

This article covers first red lesions and then hyperpigmentation.

Red oral lesions

Red oral lesions are commonplace and usually associated with inflammation in, for example, mucosal infections. However, red lesions can also be sinister by signifying severe dysplasia in erythroplasia, or malignant neoplasms (Table 1).

|

LOCALIZED

|

Inflammatory lesions

Most red lesions are inflammatory, usually:

Geographic tongue (erythema migrans)

Geographic tongue (erythema migrans) is a very common condition and cause of sore tongue, affecting at least 1–2% of patients. There is a genetic background, and often a family history. Many patients with a fissured tongue (scrotal tongue) also have geographic tongue. Erythema migrans is associated with psoriasis in 4% and the histological appearances of both conditions are similar.

Some patients have atopic allergies, such as hay fever, and a few relate the oral lesions to various foods, eg cheese. A few have diabetes mellitus.

Clinical features

Geographic tongue typically involves the dorsum of the tongue, sometimes the ventrum and, on occasions, it may affect other oral mucosal sites. It is often asymptomatic, but a small minority of patients complain of soreness and these patients are virtually invariably middle-aged. If sore, this may be noted especially with acidic foods (eg tomatoes or citrus fruits) or cheese.

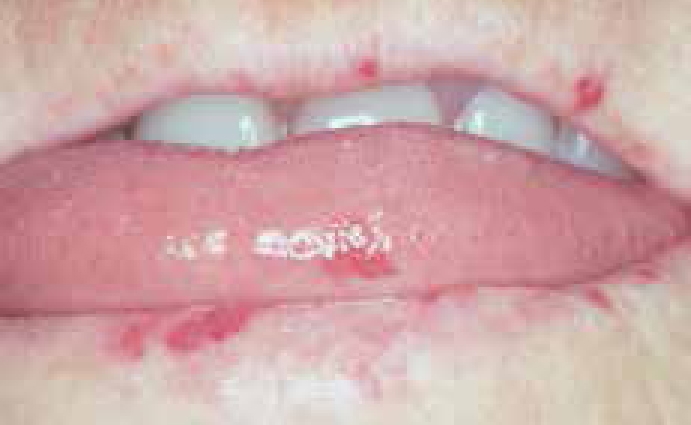

There are irregular, pink or red depapillated map-like areas, which change in shape, increase in size, and spread or move to other areas, sometimes within hours (Figure 5).

The red areas are surrounded by distinct yellowish slightly raised margins (Figure 6). There is increased thickness of the intervening filiform papillae.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of geographic tongue is clinical mainly from the history of a migrating pattern and the characteristic clinical appearance. Blood examination may rarely be necessary to exclude diabetes, or anaemia, if there is confusion with a depapillated tongue of glossitis.

Keypoints: geographic tongue

Management

Reassurance remains the best that can be given. Zinc sulphate 200 mg three times daily for 3 months or a topical rinse with 7% salicylic acid in 70% alcohol are advocated by some and may occasionally help.

Keypoints for patients: geographic tongue

Patient information and websites:

http://www.eaom.eu/files/geographic_tongue.pdf

http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/geographic-tongue/DS00819

Denture-related stomatitis (denture-induced stomatitis; denture sore mouth; chronic erythematous candidosis)

Denture-related stomatitis consists of mild inflammation of the mucosa beneath a denture – usually a complete upper denture. This is a common condition, mainly of the middle-aged or elderly; more prevalent in women than men.

Aetiopathogenesis

Dental appliances (mainly dentures), especially when worn throughout the night, or a dry mouth, favour development of this infection. It is not caused by allergy to the dental material (if it were, it would affect mucosae other than just that beneath the appliance).

However, it is still not clear why only some denture-wearers develop denture-related stomatitis, since most patients appear otherwise healthy.

Dentures can produce a number of ecological changes; the oral flora may be altered and plaque collects between the mucosal surface of the denture and the palate.

The accumulation of microbial plaque (bacteria and/or yeasts) on, and attached to, the fitting surface of the denture and the underlying mucosa produces an inflammatory reaction. When Candida is involved, the more common terms ‘candida-associated denture stomatitis’, ‘denture-induced candidosis’ or ‘chronic erythematous candidosis’ are used.

In addition, the saliva that is present between the maxillary denture and the mucosa may have a lower pH than usual. Denture-related stomatitis is not exclusively associated with infection, and occasionally mechanical irritation is at play.

Clinical features

The characteristic presenting features of denture-related stomatitis are chronic erythema and oedema of the mucosa that contacts the fitting surface of the denture (Figure 2). Uncommon complications include:

Classification

Denture-related stomatitis has been classified into three clinical types (Newton's classification), increasing in severity:

Diagnosis

Denture-related stomatitis and angular stomatitis are clinical diagnoses, although may be confirmed by microbiological investigations. In addition, haematological and biochemical investigations may be appropriate to identify any underlying predisposing factors, such as hyposalivation, nutritional deficiencies, anaemia and diabetes mellitus in patients unresponsive to conventional management.

Keypoints for dentists: denture-related stomatitis

It is best controlled by:

Management

The denture plaque and fitting surface is infested with micro-organisms, most commonly Candida albicans and, therefore, to prevent recurrence, dentures should be left out of the mouth at night, and stored in an appropriate antiseptic which has activity against yeasts (Table 2).

| Denture hygiene measures |

Cleansers containing alkaline hypochlorites, disinfectants, or yeast lytic enzymes are most effective against Candida. Denture soak solution containing benzoic acid is taken up into the acrylic resin and can completely eradicate C albicans from the denture surface. Chlorhexidine gluconate can also eliminate C albicans on the denture surface and a mouthwash can reduce the palatal inflammation. A protease-containing denture soak (Alcalase protease) is also an effective way of removing denture plaque, especially when combined with brushing.

The mucosal infection is eradicated by brushing the palate with chlorhexidine mouthwash or gel, and using miconazole gel, nystatin oral suspension or fluconazole, administered concurrently with an oral antiseptic, such as chlorhexidine, which has antifungal activity.

Keypoints for patients: denture sore mouth (denture-related stomatitis)

It is best controlled by:

Dentures should be left out overnight, so that your mouth has a rest. It is not natural for your palate to be covered all the time and the chances of getting an infection are increased if the dentures are worn 24 hours a day. Ensure you leave the dentures out for at least some time and keep them in Dentural or Steradent, as they may distort if allowed to dry out.

Special precautions for dentures with metal parts; Denclen, Dentural and Milton may discolour metal, so use with care. Brush briefly to remove stains and deposits, rinse well with lukewarm water and do not soak overnight.

Before re-use, wash in water and brush the appliance to remove loosened deposits.

Website and patient information

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1075994-overview

Neoplastic lesions: red neoplasms include:

Vascular anomalies (angiomas and telangiectasia) include:

Angiomas are benign and usually congenital. In general, most do not require any active treatment, unless symptoms develop, in which case they can be treated by injection of sclerosing agents, cryosurgery, laser excision or surgical excision.

Vesiculobullous disorders, such as erythema multiforme, pemphigoid and pemphigus, may present as red lesions (Article 2), especially localized oral purpura, which presents with blood blisters (Figure 12). Specialist referral is usually indicated.

Reactive lesions

Reactive lesions that can be red are usually persistent soft lumps (Figures 13 and 14) which include:

Specialist referral is usually indicated.

Atrophic lesions

The most important red lesion is erythroplasia, since it is often dysplastic (see below). Geographic tongue also causes red lesions (see above). Desquamative gingivitis is a frequent cause of red gingivae (Figure 15), which is almost invariably caused by lichen planus or pemphigoid, and iron or vitamin deficiency states may cause glossitis (Figure 16) or other red lesions.

Erythroplakia (erythroplasia)

Erythroplasia is a rare condition defined as ‘any lesion of the oral mucosa that presents as bright red velvety plaques which cannot be characterized clinically or pathologically as any other recognizable condition’.

Mainly seen in elderly males, it is far less common than leukoplakia, but far more likely to be dysplastic or undergo malignant transformation.

Clinical features

Erythroplakia is seen most commonly on the soft palate, floor of mouth or buccal mucosa. Some erythroplakias are associated with white patches, and are then termed speckled leukoplakia (Figure 17).

Diagnosis

Biopsy to assess the degree of epithelial dysplasia and exclude a diagnosis of carcinoma.

Prognosis

Erythroplasia has areas of dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, or invasive carcinoma in most cases. Carcinomas are seen 17 times more often in erythroplakia than in leukoplakia and these are therefore the most potentially malignant of all oral mucosal lesions.

Management

Erythroplastic lesions are usually (at least 85%) severely dysplastic or frankly malignant. Any causal factor, such as tobacco use, should be stopped, and lesions removed.

There is no hard evidence as to the ideal frequency of follow-up, but it has been suggested that patients with mucosal potentially malignant lesions be re-examined:

Purpura (bleeding into the skin and mucosa) is usually caused by:

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of red lesions is mainly clinical but lesions should also be sought elsewhere, especially on the skin or other mucosae.

It may be necessary to take a blood picture (including full blood count and platelet count), and assess haemostatic function or exclude haematinic deficiencies. Investigations needed may include other haematological tests and/or biopsy or imaging.

Management

Treatment is usually of the underlying cause, or surgery.

Hyperpigmentation

Oral mucosal discoloration may be superficial (extrinsic) or due to deep (intrinsic – in or beneath mucosa) causes and ranges from brown to black.

Causes of extrinsic discoloration include:

Black hairy tongue (Figure 18) is one extrinsic type of discoloration seen especially in patients on a soft diet, smokers, and those with dry mouth or poor oral hygiene. The best that can usually be done is to avoid the cause where known, and to advise the patient to brush the tongue or use a tongue-scraper.

Causes of Intrinsic discoloration are summarized in Table 3.

|

Localized

|

Localized areas of pigmentation may be caused mainly by:

Keypoints: single hyperpigmented lesions

Generalized pigmentation, often mainly affecting the gingivae (Figure 24) is common in people of colour, and is racial and due to melanin. Seen mainly in black and ethnic minority groups, it can also be noted in some fairly light-skinned people. Such pigmentation may be first noted by the patient in adult life and then incorrectly assumed to be acquired.

In all other patients with widespread intrinsic pigmentation, systemic causes should be excluded. These may include:

Diagnosis

The nature of oral hyperpigmentation can sometimes only be established after further investigation.

In patients with localized hyperpigmentation, in order to exclude melanoma, radiographs may be helpful (they can sometimes show a foreign body) and biopsy may be indicated, particularly where there is a solitary raised lesion, a rapid increase in size, change in colour, ulceration, pain, evidence of satellite pigmented spots or regional lymph node enlargement. If early detection of oral melanomas is to be achieved, all pigmented oral cavity lesions should be viewed with suspicion. The consensus of opinion is that a lesion with clinical features, as above, seriously suggestive of malignant melanoma, are best biopsied at the time of definitive operation.

In patients with generalized or multiple hyperpigmentation, Specialist referral is indicated.

Management

Management is of the underlying condition.