References

Mandibular radiolucencies – how to refer and manage appropriately

From Volume 45, Issue 5, May 2018 | Pages 434-438

Article

Radiolucencies may be detected in either the maxilla or mandible during routine examination and can arise from odontogenic or non odontogenic causes. A radiographic survey at primary care level may be limited to intra-oral periapicals owing to the lack of justification for dental panoramic tomograms (DPTs). The purpose of this paper is to discuss three different referrals of mandibular radiolucencies, which were investigated at Whipps Cross University Hospital, following referral from GDPs. The paper will explore the presentation, imaging and management of the cases.

Case 1

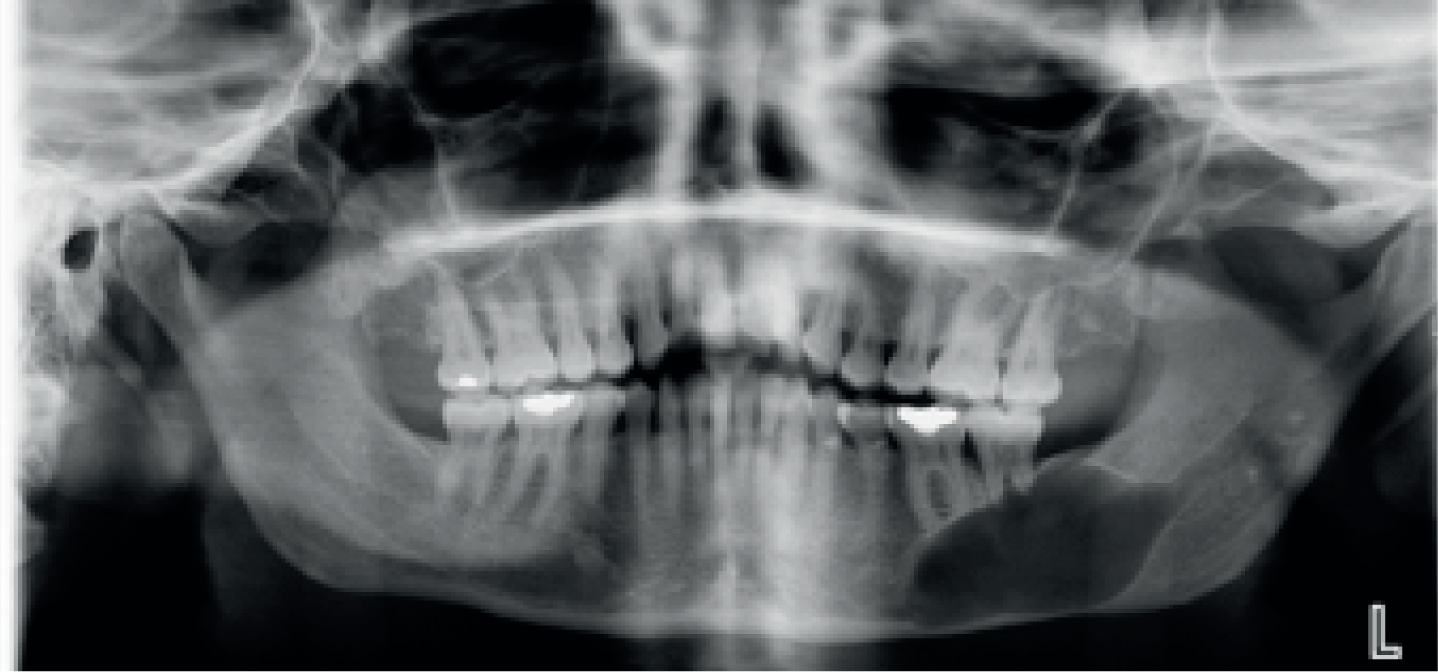

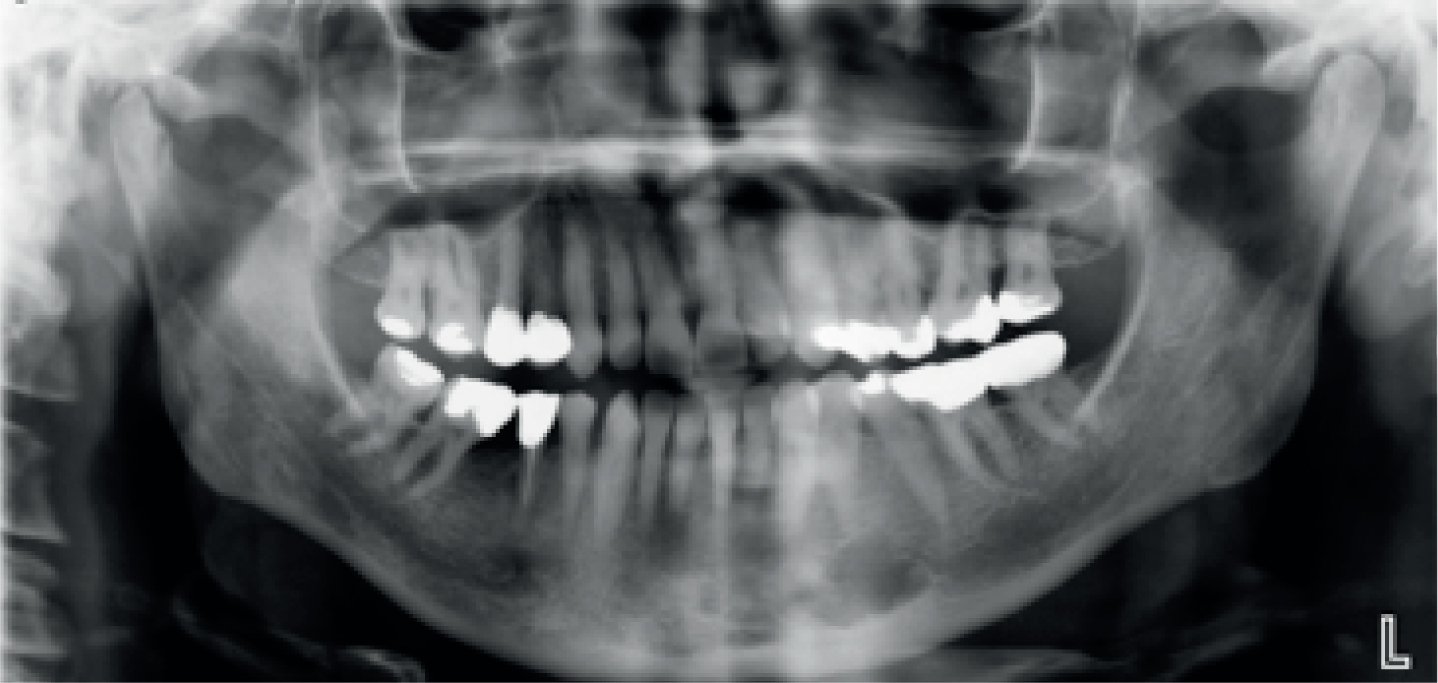

A 46-year-old lady was referred by her dentist due to an unknown left mandible radiolucency, associated with mobility of her LL7. She was a smoker but medically fit. Extra-oral examination was unremarkable, and intra-orally there was a no bony expansion or swelling of the left mandible. There was no paraesthesia along the distribution of the inferior alveolar nerve. The LL7 was grade 1 mobile but responded positively to ethyl chloride testing. The DPT (Figure 1) revealed a well demarcated, wine goblet-shaped radiolucency in the left body of the mandible extending from the LL6 to LL8 region. It appeared to be intimately related to, and in continuity with, the left inferior alveolar canal. The roots of the LL6 and LL7 appeared resorbed, although there did not appear to be any significant periodontal disease-related bone loss around either LL6 or LL7.

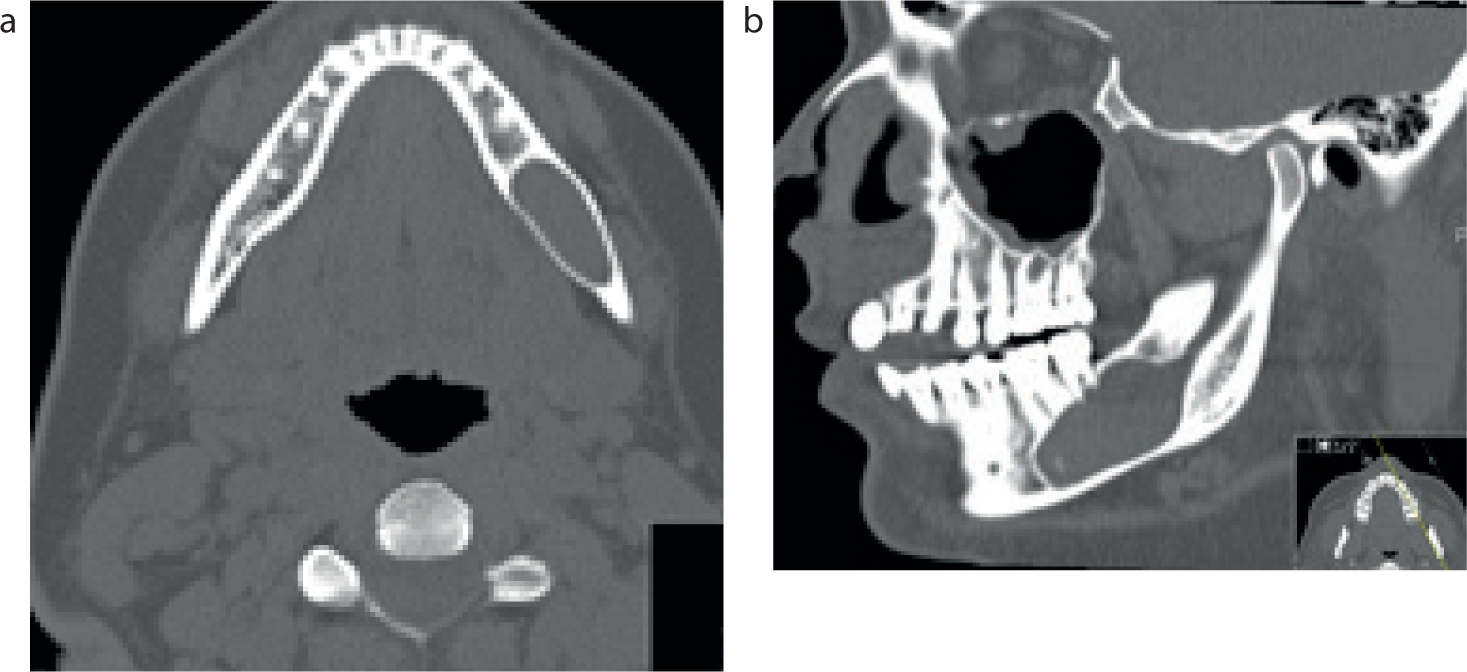

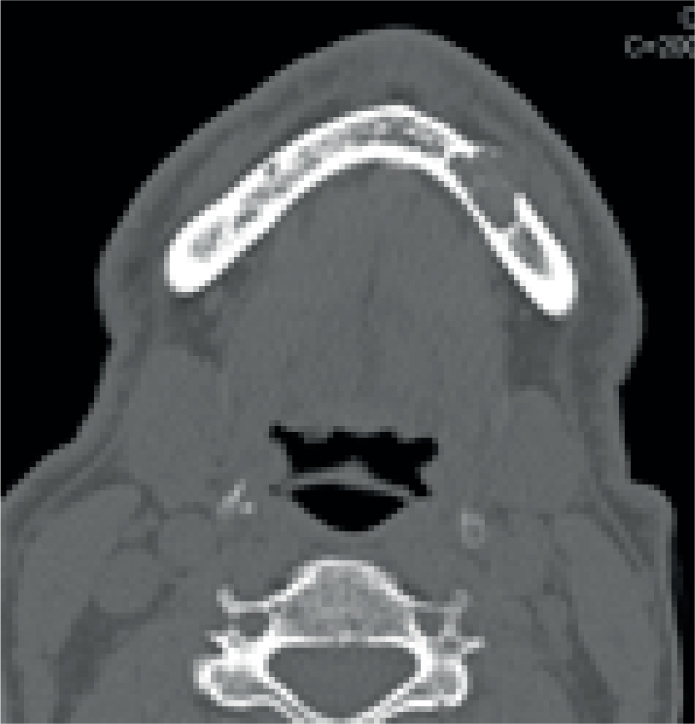

Under local analgesia, extraction of the LL7 with simultaneous biopsy and marsupialization of the left mandibular radiolucency were carried out. The biopsy confirmed a spindle cell neoplasm. A CT mandible scan (Figure 2) was organized, followed by an MRI scan at the recommendation of a consultant radiologist. The MRI scan report revealed ‘marked expansion of the left inferior dental canal over a distance of approximately 3.5 cm. The expansion of the canal is due to a soft tissue mass which shows moderate slightly non uniform enhancement consistent with a neurogenic tumour. It is not possible to distinguish the inferior dental nerve separately from the mass’.

The neoplasm was excised shortly afterwards. The final excision biopsy revealed an intraneural perineuroma (benign peripheral nerve sheath tumour). The patient was reviewed one month post-operatively and healing was progressing well and further review has been arranged. Surprisingly, there was no neurological deficit to the lower lip.

Case 2

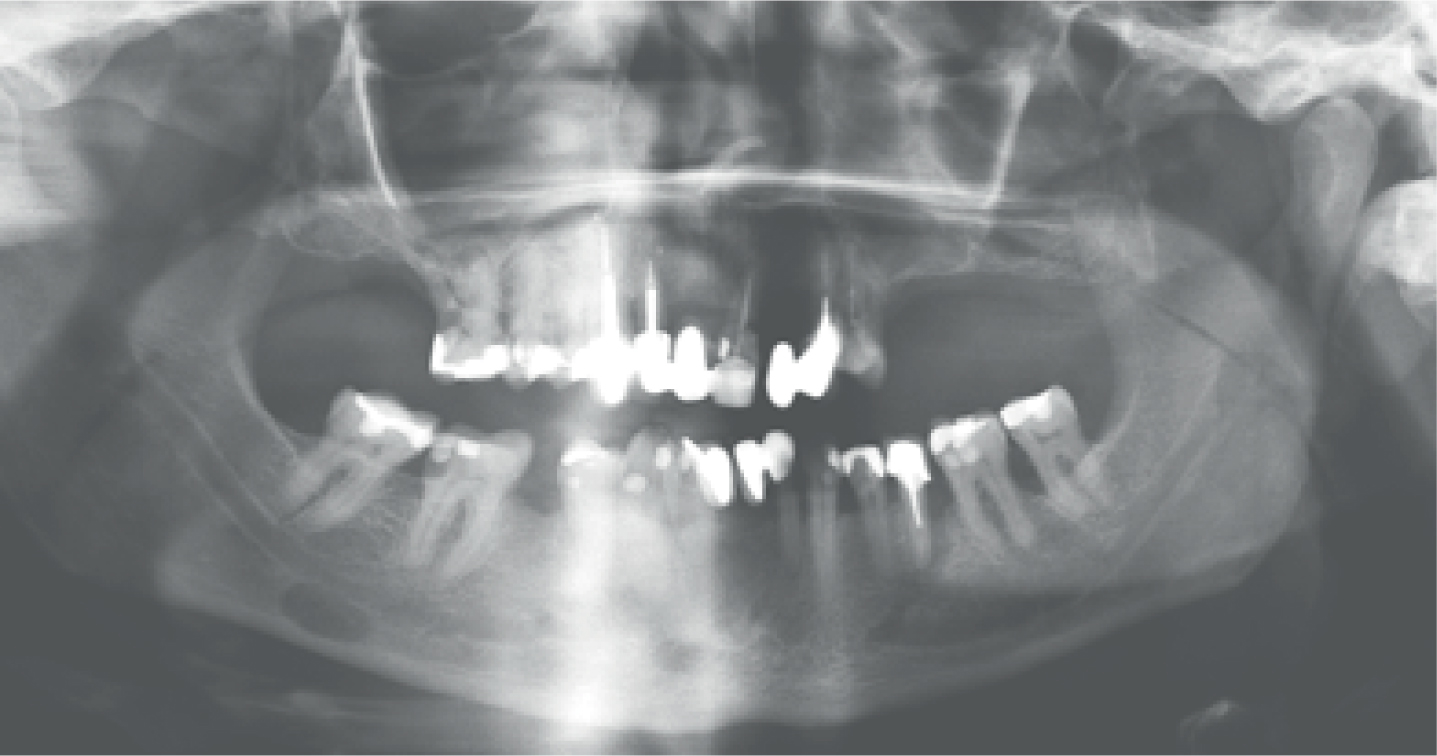

A 54-year-old gentleman was referred by his GDP, who noted on a DPT a radiolucency in the right body of mandible. There was no history of pain or swelling. A well demarcated, uniformly radiolucent ovoid lesion in the right body of the mandible was confirmed on the DPT (Figure 3), below the LR6 and LR7, lying beneath the inferior alveolar canal. It was well away from adjacent teeth. CT imaging (Figure 4) was requested and the coronal CT slice showed the lesion had breached the lingual plate.

A diagnosis of Stafne's bone cyst was made and therefore no treatment was required as this stage. The patient is under regular review within the department.

Case 3

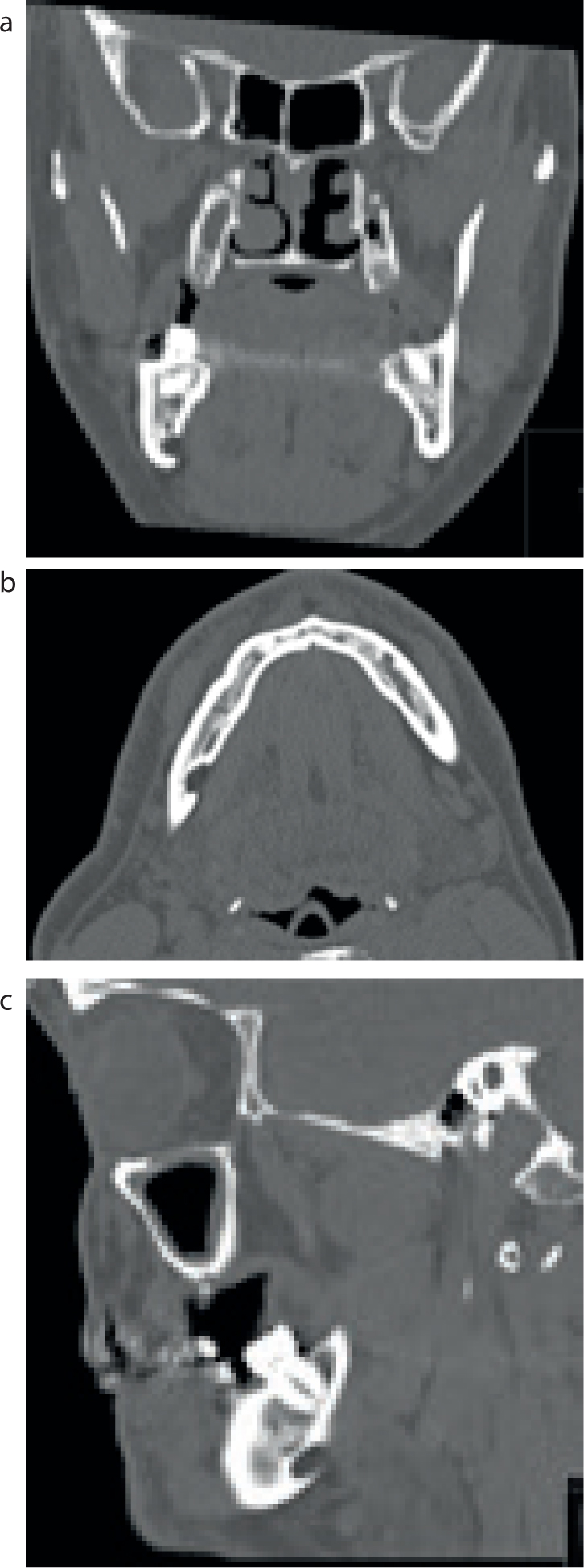

A 69-year-old gentleman was referred by his GDP with an asymptomatic left anterior mandible lump which had been present for one year. His medical history was clear. On examination, a mild fullness in the left parasymphysis region was noted. A DPT (Figure 5) was carried out. Indeed, a lower occlusal radiograph could have been an alternate radiograph, had it been available within the unit. Subsequently, a CT mandible (Figure 6) revealed a 1.7 cm abnormality in the anterior left mandible, which contained some calcification and was causing expansion of the bone.

Following an incisional biopsy of the lesion under local anaesthesia, it was discovered that the lesion was in fact an intrabony arteriovenous malformation. An MRI angiogram confirmed a slow flow vascular malformation which had not changed over 9 months. Following a discussion with the patient, the lesion was excised under general anaesthesia. Healing is progressing well with no sensory deficit.

Discussion

Radiolucencies occurring in the mandible can be detected during routine radiographic examination in dental practice. Referral of radiographs to a dental radiologist for further review of images can be arranged if this service is available (for example, within dental hospitals), to help avoid referral to secondary care surgical units. If a diagnosis can be reached via this route, this can also help avoid excessive imaging and exposure to high dose CT scans. District general hospitals will generally not have direct access to a dental radiologist.

Intraneural perineuromas are rare benign tumours of peripheral nerve sheaths. A systematic review in 2007 showed 51 documented cases and only 5 occurring in the oral region.1 Only 25% of the patients with documented perineuromas experienced any form of sensory deficit. The lack of symptoms from such a lesion can lead to late presentation, and surgery is therefore carried out when the lesion has already grown to a significant size. The treatment of choice recommended was complete excision of the lesion. Post-operative follow-ups of 35 of the 51 perineuromas revealed no further recurrence, with a median follow-up of 72 months. Perhaps most surprisingly, given their intimate relationship to the origin nerve, 86% of patients who undergo resection do not experience any neurological deficit.2

Stafne's bone cysts are asymptomatic, unilateral mandibular bony defects.3 Characteristically, they usually occur in the posterior mandible, below the inferior alveolar canal and in the lower third molar region. They are therefore usually picked up on routine radiographic examination, given that they rarely cause symptoms.4 They are most commonly detected in men in their fifth to seventh decade, with a quoted incidence of 0.1% to 0.48%.5 Although it is not known exactly why they occur, some theories suggest that they form as a result of pressure on the lingual plate from the submandibular gland.

Vascular malformations in the head and neck region are extremely rare. When occurring in the maxilla or mandible, they are usually intraosseous, and therefore give rise to very few symptoms. If disturbed during surgical procedures, these vascular malformations can cause dramatic bleeds. Most commonly, patients with such lesions will experience a degree of paraesthesia, soft tissue swellings, and mobility of teeth.6-7 Two common classifications for arteriovenous malformations are high flow and low (slow) flow. High flow lesions require rapid treatment to avoid potentially fatal bleeding episodes. Slow flow lesions do not require such urgent treatment, however, they should be monitored closely. The recommended treatment for high flow lesions is embolization, and subsequent surgical excision.8,9

Imaging techniques employed at secondary level can include cone beam computer tomography (CBCT) in the first instance, with CT and MRI also available if required. In Case 1, upon reflection, a cone beam CT could have been employed as the secondary imaging modality following a DPT, as opposed to a CT and MRI scan. In Case 2, a DPT would have sufficed as the only imaging modality used. As in Case 1, should further imaging have been required, a cone beam CT would have been effective, as opposed to a full CT. It is vital that appropriate scans be organized for such patients, as this helps form a successful management plan. Selecting the most appropriate scan will also help reduce undue radiation for patients. Organization of more complex scans, such as MRA (Magnetic resonance angiogram) can be planned with the advice of a senior colleague within the department.

Most mandibular radiolucencies detected in a general dental practice can be diagnosed at local level. Case 2 is a classic example of a Stafne's bone cyst and could have been diagnosed at local level. The cases reported in this paper highlight rare conditions, which needed appropriate secondary care management. It is prudent for GDPs to be vigilant when carrying out oral and radiographic examinations and to pay attention to any abnormalities detected. As described here, the clinical detection of a mild oral swelling could well result in a diagnosis of a condition requiring rapid assessment and management in a surgical department. The three cases here were all referred appropriately on a non-urgent pathway (non-cancer pathway), with a good level of clinical information in the referral letter. It is highly beneficial to the receiving clinician if radiographs and results of clinical examinations, such as vitality testing, are attached to the referral letter, if appropriate.

As shown, correct referral from a GDP at an early stage can result in quick diagnosis and help avoid potentially major complications.