References

A case of florid pregnancy gingivitis

From Volume 46, Issue 2, February 2019 | Pages 166-170

Article

There is consensus that physiological changes may occur in a person's periodontium during pregnancy1, 2 The expectant mother must adapt to the changes that occur during the period of pregnancy.3 The most noteworthy physiological change is the increase in production of the androgens, specifically the hormones oestrogen and progesterone. These steadily increase until the eighth month of pregnancy when progesterone remains constant and oestrogen continues to increase during the luteal phase.3 The increase in hormones is due to the placenta, which controls production in early pregnancy from the luteal phase (which results from the implantation of the embryo).3, 4 The oestrogen levels rise to more than 100 times by the time of birth, then during labour, with the placenta withdrawn, there is a significant decrease in the levels of both progesterone and oestrogen. Within 2−3 days post-partum, the levels of these hormones are reduced to those found pre-pregnancy.3

Androgens have roles in the vascular system during pregnancy, maintaining the endometrium and helping in the production of milk in the mammary gland.3 They also increase the basal metabolic for the foetus and help regulate the immune system in the pregnant mother.3

The significant rise in androgens during pregnancy appears to be associated with increased levels of gingival problems.4 There are numerous studies which show an increased prevalence of gingivitis during pregnancy from 35% to 100%.5 Despite no significant difference in plaque, there is a higher chance of gingival inflammation during pregnancy compared with post-partum.6, 7 In addition, there have been documented changes in the microbial community, vascular and cellular composition and immune function that may all adversely affect the periodontium.8

Case report

A 26-year-old woman was referred to the University Hospital Wales (UHW) from her general dental practitioner (GDP) with the principal complaint of sore and swollen gums and, in addition, difficulty in eating. The medical history revealed an iron deficiency anaemia for which she was taking iron supplements only and no other medication. The patient did not smoke or drink alcohol. The patient presented at 33 weeks pregnant.

Several months earlier the patient's GDP advised improvement in oral hygiene which had limited success, and subsequently there had been an increase in swelling, especially in the maxillary left and anterior sextants, whereby the tooth crowns were becoming obscured. The GDP also provided two courses of ultrasonic scaling with no noted improvement. Occasional use of over-the-counter analgesics had little effect.

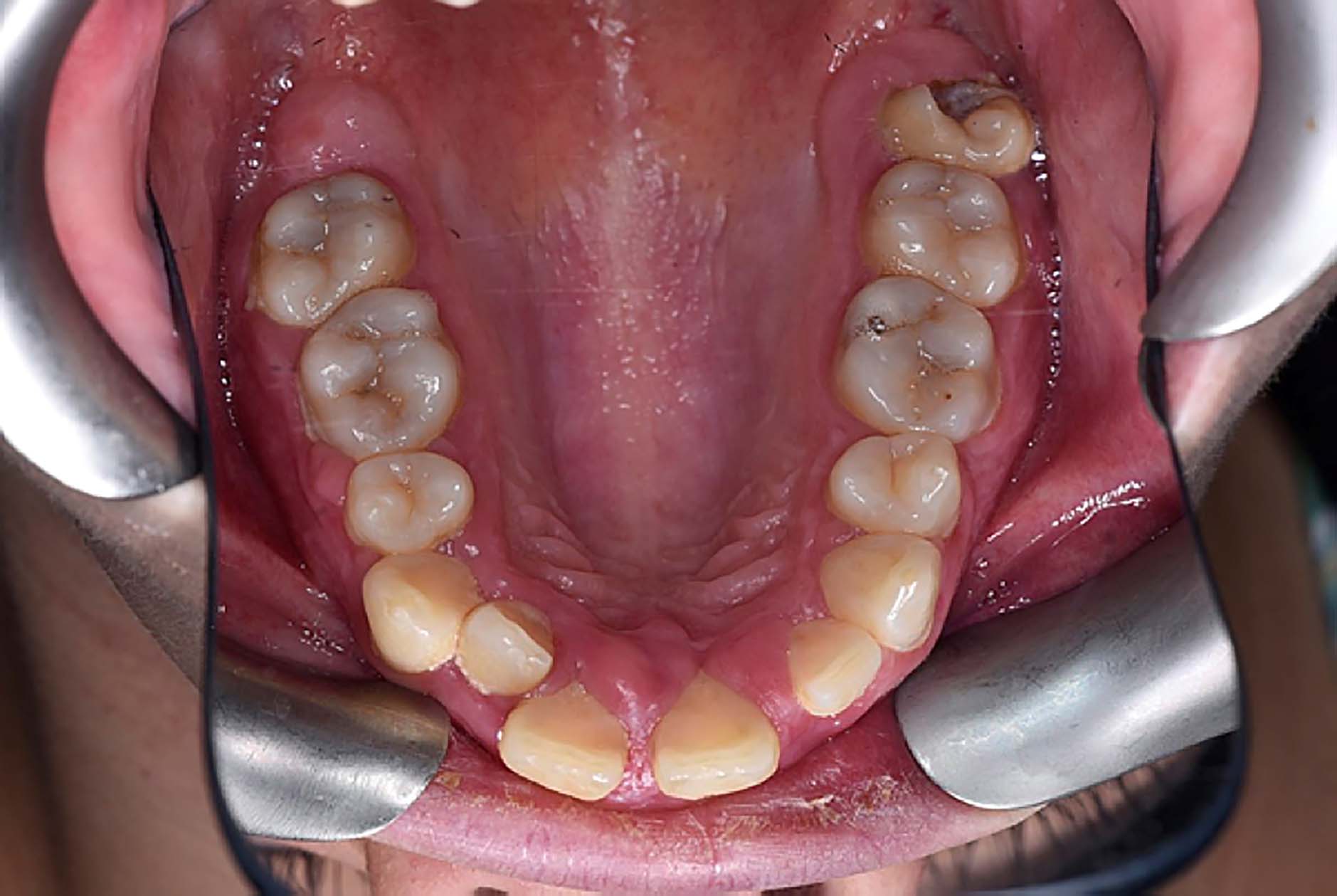

Intra-oral examination revealed obvious oedematous and erythematous gingivae which were fibrous in nature. Additionally, there were two skin soft tissue lesions, one situated at the vermilion border of the upper lip and the second superior to the right eyebrow (Figure 1). On questioning, it was apparent that these lesions had appeared at a similar time to the gingival overgrowth. Intra-oral examination showed visible plaque and debris concomitant with an inability to perform any meaningful oral hygiene practices due to the discomfort and swelling. There was marked generalized gingival swelling, especially to the maxillary labial segment, with enlarged interdental papillae (Figures 2 and 3). The mandible, although suffering generalized gingivitis and some papilla swelling, did not have the same florid appearance. The basic periodontal examination showed scores of 4 in all sextants. The GDP did not note any severe periodontal disease prior to this episode, apart from generalized gingivitis.

The diagnoses based on clinical features and history were pregnancy-induced gingival inflammation, pregnancy epulides with two separate extra-oral pyogenic granulomata. The patient was understandably alarmed at the diagnosis, although this was mentioned to the patient as a differential diagnosis by her GDP. It is important to stress that reassurance is a key part of the management of these conditions, and clinically much of this presentation can be self-limiting post-partum.

Initial minimal interventions provided included use of Benzydamine Hydrochloride (DifflamTM) mouthrinse to counter the oral soreness, chlorohexidine gluconate (CorsodylTM) gel and use of a soft brush to optimize plaque control. Two weeks later the patient underwent review and, at that point, light supra- and subgingival debridement was performed under local anaesthesia. A decision was made not to perform any further intervention until post-partum.

The patient was reviewed 6 weeks after conclusion of her pregnancy. The gingival condition had already started resolving, although unsightly maxillary anterior overgrowth remained and appointments for surgical removal and recontouring were made (Figures 4 and 5). This was completed in one visit utilizing local anaesthesia and the use of both Blake knives and electrosurgery instrumentation in order to recontour the anterior periodontium and achieve haemostasis.

Post-operative healing was unremarkable, indeed near complete resolution of the periodontal inflammation had occurred, leaving the patient with pre-existing incisor diastemata which were reduced utilizing local resin restorations (Figures 6 and 7).

Discussion

Pregnancy gingivitis

Pregnancy gingivitis is defined as ‘a non-specific, vascularizing, and proliferative inflammation with large amounts of infiltrated inflammatory cells’.3 During pregnancy, there is an exaggerated response to dental plaque which leads to swollen gingivae which can bleed easily on brushing. Despite this response, during pregnancy there is no histological difference from that which develops in non-pregnant individuals.9

Although pregnancy itself does not cause gingivitis, it may aggravate pre-existing gingival disease.10 Pregnancy gingivitis typically presents as a dark red colour, smooth but swollen contour with bleeding on minor trauma. These gingival changes have been described as resolving within a few months post-partum, but only if local irritants are eliminated. Pregnancy gingivitis may develop into more severe vascular lesions (namely pregnancy epulis, pregnancy tumour or pyogenic granuloma). Epidemiological studies of pregnancy gingivitis show a prevalence ranging from 35% to 100%.5

Pregnancy epulis

Pregnancy epulis (pyogenic granuloma of pregnancy, pregnancy granuloma, epulis gravidarum) is a ‘localized, soft, overgrown lesion which develops on the gingiva in up to 5% of pregnancies.’3 This is usually bright red in nature due to its vascularity. These can be pedunculated or sessile. In the aforementioned case, there were unusually large 1.5 cm pedunculated lesions in the maxillary region. This case therefore is an example of significantly more florid and extensive gingival reactions than those commonly reported.

Pregnancy epulis is a reactive lesion, usually to local irritation or trauma and, in spite of the terminology, is neither a true neoplasm nor a true granuloma. Raber-Durlacher et al showed that the increase in hormonal activity results in an intense inflammatory response to dental plaque and selective growth of specific periodontal pathogens, including Prevotella intermedia.11 The literature suggests that Prevotella intermedia utilizes androgens as a nutrition source, which may account for the increase in expression of this species in dental plaque during pregnancy.11

Clinically, pregnancy epulis manifests as a mass of vari=able size that has a tendency to bleed and may also interfere with mastication. With the levels of androgens normalizing post-partum, the pregnancy epulis generally resolves without treatment. Some may undergo a fibrous maturation and then resemble a fibroma. If the mass still persists, then surgical removal may be performed for aesthetic reasons. Cardoso's case series of 41 lesions demonstrated that the majority of pregnancy epulides are confined to the gingivae (70%), 7% to the lip and 5% other areas.12 Moreover, Krishnapillai et al found 94 of over 200 pyogenic granuloma lesions were gingival in their presentation. Furthermore, only 18 of these cases occurred in pregnant women.13

Apart from three exceptions Ababneh, McIntosh and Yamoah et al in the preceding decade, there have been very few florid or diagnostically challenging cases reported.14, 15, 16

Treatment regimens

There are few immediate treatment options for patients in this situation. Meticulous oral hygiene is clearly desirable with emphasis on interdental and, where possible, subgingival cleaning. Anaesthetic mouthwashes can play a part in oral soreness and aiding mastication. Antiseptic mouthwashes are used when there are difficulties in performing adequate plaque control.

Residual enlarged lesions which remain post-partum may, however, require surgical correction, from both a cosmetic and hygiene perspective. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice if the gingival lesion is persistently traumatized during toothbrushing or is unaesthetic. This is not likely to be first line treatment during the pregnancy and should be delayed until post-partum where possible. Exceptions may include unavoidable trauma from opposing teeth resulting in pain or bleeding,17 if it is affecting the patient's speech and/or mastication.18 This, in conjunction with the reported high recurrence rates of the lesion, means that surgery should be completed once the lesion has regressed as much as possible spontaneously post-partum.17 Any reduction in inflammation and swelling which occurs post-partum will also facilitate subsequent gingival surgery.

Gingivectomy is the complete removal of the soft tissue wall of the pocket.19 Despite being superseded by other more conservative surgical techniques, it still remains the treatment of choice for recontouring irregular tissues, especially in overgrown gingival tissues.20 Protocol might dictate tissue marking with a periodontal probe or marking forceps (Crane Kaplan), which act as a guide for the surgical procedure. Number 12 or 15 scalpel blades might suffice but, due to the unique access and angulation, specific gingivectomy blades such as Kirkland, Orban and Blake knives allow a more anatomically correct ‘bevelled’ approach.19

The incision is made to the markings placed earlier at a 45-degree angle from apical to the base of the pocket in a continuous incision. It is important to make sure that the correct incision is made for the best aesthetic outcome; too flat a contour will produce a compromised aesthetic result.19 Sharp curettes are used to remove the tissue and further root surface debridement is done to remove any residual calculus deposits. Wound healing takes around 7−14 days as epithelial cells cover the wound, keratinizing after 14−21 days.19 New epithelial attachment at the root surface takes roughly 28 days to form. As illustrated in Figures 6 and 7 (3 week post-operatively), the gingival aesthetics are much improved. Electrosurgical or laser interventions have been suggested as beneficial if only to control predicted profuse haemorrhage.

A review covering different fields, including the obstetrical and gynaecological community, has discussed the diagnoses and management of these lesions.21 Geisinger et al have shown that tailoring oral hygiene advice to this set of patients has helped to reduce the incidence of gingivitis during pregnancy.20

In comparison, Scully and Porter reported a more routine case of pregnancy gingivitis which was exacerbated by chronic gingivitis. This led to a small localized pregnancy epulis which was comparatively mild against our highlighted case.22

Conclusion

This paper aims to inform readers about this presentation and to reassure patients that much of the lesion may heal spontaneously post-partum, despite the unsightly appearance. With early diagnosis, referral to a specialist, emphasis on reassurance, maintenance of impeccable oral hygiene and possible surgical technique post-partum, a desired functional and aesthetic result can be achieved.