References

Practice-Based risk assessment − a practical guide for oral healthcare teams: tooth wear

From Volume 46, Issue 2, February 2019 | Pages 171-178

Article

Tooth wear is a multi-factorial, complex process involving erosion, attrition and abrasion.1 Erosive tooth wear is a term commonly used by European colleagues to represent that severe tooth wear rarely occurs without an underlying erosive aetiological component. Dental erosion is described as the loss of tooth tissue due to the effects of acid only, whilst attrition and abrasion describe the involvement of tooth-to-tooth and tooth-to-foreign object contact, respectively. Current evidence indicates erosive tooth wear is common and the prevalence is increasing, particularly in younger age groups.2, 3

Patients with erosive tooth wear can be difficult to risk assess as they are often unaware of their condition and may not see their dentist until their tooth wear is significantly advanced. Being able to risk assess patients when they do present is necessary to minimize the progression of erosive tooth wear.

Risk assessing erosion

This involves determining the potential origin of the underlying acids affecting patients' teeth. These can be categorized into either intrinsic acids and/or extrinsic acids.

Intrinsic acids (gastric contents)

Erosive tooth wear can result when stomach contents, containing gastric juice, enter the oral cavity frequently. The most common medical conditions resulting in erosive tooth wear from stomach acid are gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) and vomiting-associated eating disorders (such as bulimia nervosa) affecting roughly 10% and <1−2% of the global population, respectively.4, 5 Most patients suffering from GORD are symptomatic and will commonly complain of acid reflux and/or sternal pain. Management from their GP should be encouraged to control the condition. The absence of symptoms does not necessarily mean that reflux is not involved. Silent gastro-oesophageal reflux can be a chronic long-term condition which remains symptomless, but the oral effects of the gastric acid reflux may be the only clinical sign. Other, more rare, causes of gastric contents entering the oral cavity include rumination habits, whereby patients voluntarily regurgitate their food in order to rechew it and vomiting caused by other factors.6 Pregnancy may also cause vomiting, particularly during the first trimester, and hyperemesis gravidarum is a condition, affecting 0.3%−2% of the population whereby vomiting starts early in the pregnancy and may last the duration of the entire pregnancy.7 In addition, pregnant women are more prone to reflux.

Certain medications may have a central emetic effect, such as chemotherapeutic drugs, opioids, digitalis and some oestrogens.8 Alcoholism may also predispose to both vomiting and reflux disease.9 With all these conditions, temporary periods of acid exposure are unlikely to result in severe pathological tooth wear, however, if they become chronic and uncontrolled, severe erosive tooth wear may result.

Eating disorders with an ongoing vomiting component can be challenging to assess from a patient history, given the unfortunate stigma attached to the associated mental health issues. Encouraging patients to discuss their current patterns regarding the frequency of vomiting, oral hygiene procedures before and after vomiting, and their diet will facilitate practical risk management while emphasizing a supporting role.

Difficulty arises if an eating disorder is suspected but not diagnosed, particularly as those with eating disorders may consume excessive amounts of diet drinks during bulimic phases, confounding the diagnosis between extrinsic and intrinsic erosive tooth wear. Erosive tooth wear may or may not be present in these patients. If present, it is often most severe on the palatal surfaces of the maxillary arch but generalized wear can be observed on all dental surfaces. Although there can be clinical indicators when the disease is active, such as enlargement of the parotid glands, soft tissue scarring on the backs of fingers, where vomiting is forced with the hands and bruising or soft tissue damage on the hard and soft palate, it is difficult to risk assess and manage patients without an open conversation about the severity of their condition.

When risk assessing erosive tooth wear resulting from intrinsic acids, the frequency of acid entering the mouth is likely to be one of the key indicators of progression, although there are few clinical studies to confirm this.10 Patients that are aware of weekly episodes of acid exposure can be classified as high risk of intrinsic erosive tooth wear progression. Those who experience acid exposure less than weekly may be considered as medium risk, whilst those that rarely experience acid exposure, due to good disease control, may be considered low risk.

Extrinsic acids (diet)

The frequency of dietary acid intake has been shown as the most significant predictor of dietary erosive wear.11, 12 A recent case-control study reported that less-than-daily acid intake was associated with a negligible risk of wear.11 The risk increased when dietary acids were consumed more than once daily and further increased by 13-fold when three dietary acids or greater were consumed per day.11 Common diet foods include fruits, fizzy drinks (excluding plain sparkling water), energy drinks, juices and smoothies. However, it also includes lesser known dietary acids such as fruit teas, fruit additions or flavourings in drinks, eg a slice of lemon or cordial/squash, sports drinks, fruit-flavoured lozenges or sweets, some medications, particularly effervescent vitamin C tablets. A patient who takes an effervescent multivitamin drink in the morning, has an apple as their mid-morning snack, takes a juice at lunchtime and then has a fruit tea that evening has had four acid attacks that day. The risk of developing erosion is reduced if acids are taken at meal times and this supports the current advice on balanced and healthy diets. Consuming fruit with meals showed no increased risk of erosive wear progression compared to those who snacked on fruit between meals. Similarly, those who drank acidic drinks with meals were half as likely to have severe erosive tooth wear than those who consumed the same frequency of acidic drinks between meals.11

Drinking habits such as sipping, swishing or holding drinks in the mouth prior to swallowing increases the risk of having tooth wear.13 There are rare occupational/recreational histories that might contribute to an increased risk of erosive wear, such as wine tasters,14 athletes due to their need for hydration with erosive beverages containing electrolytes,15 or those with occupations or recreational habits associated with increased intake of caffeinated drinks or soft drinks, such as long-distance driving, night shift working or video-gaming.16, 17

Risk assessment can be categorized according to patients' daily habitual behaviour. If they consume three or more dietary acids per day or greater than two dietary acids per day between meals, then they should be categorized as high risk. Daily acidic drink intake with meals would categorize them as medium risk and less than daily acid intake or daily fruit intake with meals places them in a low risk category. Patients should also be categorized as high risk if they have a habit of holding things in their mouth/cheeks prior to swallowing, sipping acidic drinks slowly or rinsing drinks around their mouth.

Risk assessing attrition

Bruxism is defined as an oral habit consisting of involuntary rhythmic or spasmodic non-functional gnashing, grinding, or clenching of teeth, other than chewing movements of the mandible, which may lead to occlusal trauma.18

Diagnosis of bruxism at early stages can be difficult as many patients are not aware of their habit. Jaw muscle discomfort, fatigue, pain, jaw lock, particularly upon awakening, have been reported by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine as being indicative of sleep bruxism. Often a sleep partner may be able to give evidence that the patient audibly or visibly bruxes at night. A comprehensive pain history involving the location, duration, precipitating factors, severity of the pain, relieving factors and where it radiates to can assist in the diagnosis of muscular or joint pain. The patient may give a history of chipping or fracturing restorations or cusps or both. In severe parafunction, occlusal loading can result in dental hypersensitivity. Occupation and lifestyle should be assessed for stress levels. Current or historical recreational drug use should be investigated, if appropriate. The medical history should be checked for GORD symptoms, sleep apnoea or medications which may cause bruxism.

The risk assessment of bruxism starts with an extra-oral examination. Masseteric hypertrophy may be visible in chronic cases and the facial height may be reduced if the tooth wear has resulted in a reduced intra-oral occlusal vertical dimension. There may be reduced or asymmetric range of motion of the mandible, particularly in the morning. Clicking or crepitus of the joints may also indicate increased activity. Overactive muscles of mastication may or may not be tender on palpation and, if symptoms are present, they may assist in the diagnosis. The temporalis muscle can be particularly tender when a clenching habit is present as it is more actively involved in the final positioning of the mandible. However, the masseter may be tender for both grinding and clenching. An intra-oral palpation of the medial pterygoid is not a particularly sensitive test as it can be painful even in cases of normal mandibular activity. Often though there are no clear symptoms and the diagnosis relies upon the clinical signs.

Intra-orally, there can be soft tissue signs such as petechial haemorrhages, white lines of keratinization on the buccal occlusal line, crenations on the tongue, broken or chipped restorations or cusps. Dental wear facets, showing the location of interdigitation with the opposing arch, may also be visible. In severe bruxism cases, the occlusal surfaces are flat.

In addition to history taking and clinical examination, specialized devices have been used to attempt to detect a bruxism habit. These include wear on occlusal splints or for research purposes, sensors attached to occlusal splints and home muscle activity tests can be used. More advanced methods include electromyographic (EMG) recording of masticatory muscle activity in addition to the gold standard of polysomnography on sleep clinics.

Although the presence of attritional tooth wear is a confirmatory diagnosis, several studies have shown that the severity of bruxism is not related to the severity of tooth wear,19, 20 which perhaps indicates that other tooth wear aetiological factors may be at play. However, if severe attritional wear is present, particularly at a young age, the patient should be categorized as high risk.

Risk assessing abrasion

Abrasion is defined as an abnormal wearing away of the teeth by causes other than mastication.18 Any foreign body misused or overused in the mouth has potential to be an aetiological factor. This includes chewing on pens, biting fingernails or any other foreign object, holding things between the teeth on a habitual basis, oral piercings and using items as toothpicks. A commonly quoted form of abrasion is from oral hygiene procedures.21 Normal forces used to brush teeth with a low abrasivity toothpaste is unlikely to cause tooth wear.22 However, heavy pressure applied to the teeth from a brush has the potential to cause wear.22 It remains unknown what force makes the abrasion risk severe and the diagnosis primarily relies on the clinical appearance of any lesions present.

Toothpaste abrasiveness is measured by a value known as the relative enamel abrasivity (REA) or relative dentine abrasivity (RDA). As dentine is more susceptible to abrasion due to its lower mineral content, the RDA value is the widely used measure of abrasivity. An RDA over 100 is classified as high abrasivity and anything over 150 (predominantly found in whitening toothpastes) can be classified as harmful. Unfortunately, RDA testing is mandatory only in the US and not the UK/EU. Therefore, many toothpastes on the market, outside these geographical areas, do not have a known RDA value.

Studies have observed a relationship between the use of a hard toothbrush and an increase in tooth wear.12 However, it is a difficult topic for clinical research. People who choose hard toothbrushes may be more likely to brush more aggressively and with a more abrasive toothpaste to get a clean feeling. Laboratory studies have shown that increased tooth wear is associated with increased toothpaste abrasivity and increased force but not bristle stiffness.23, 24 Several studies have shown that increased tooth wear was observed with a soft toothbrush. This was thought to be due to the increased flexing of the bristles which would hold more of the abrasive toothpaste. The combination of a medium bristled toothbrush and a low abrasivity toothpaste was observed to show the least tooth wear on both enamel and dentine in the laboratory.25

A history of aggressive toothbrushing with a soft toothbrush may place patients at high risk. Dentine is more susceptible to mechanical forces than enamel and multiple studies have shown relationships between gingival recession and tooth wear.26, 27 Any exposed dentine will place patients in a higher risk category for a combined acid/mechanical wear challenge.

Not everybody uses a toothbrush and toothpaste to clean their teeth. Chewing on bark, sticks or using cloth with powders or salts is used in several countries to clean teeth and there is evidence of their efficacy for plaque removal. However, these can be very abrasive and have also been associated with increased tooth wear.28 It is important to recognize that patients may be more comfortable using these oral hygiene procedures. In the absence of a daily acid source they may be categorized in the medium risk category.

BEWE − screening wear already present

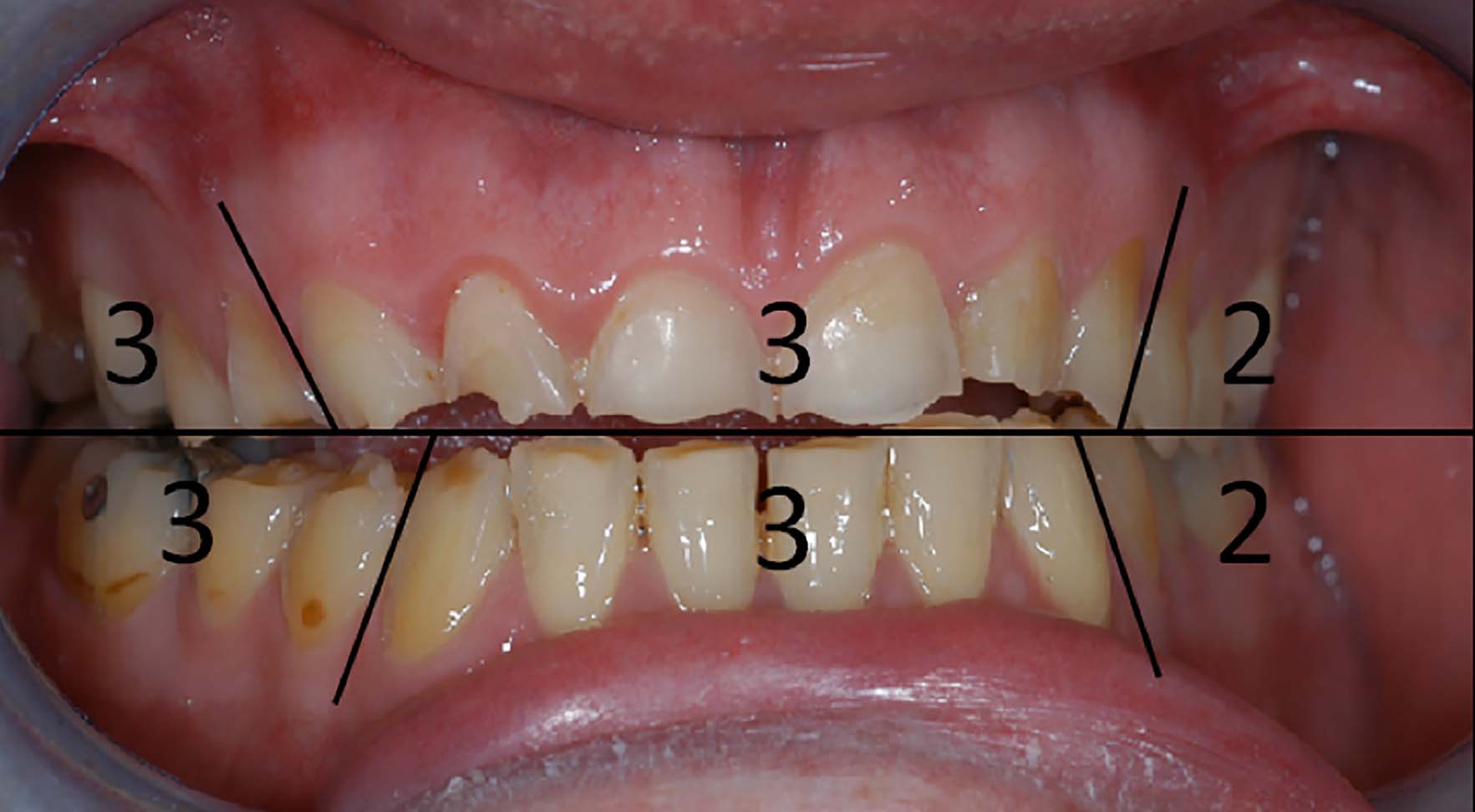

In today's society, it is difficult to justify not screening for tooth wear, not only to record it but also as part of a risk assessment. A useful tool for this is the Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE), developed through international consensus, as a tool for screening erosive tooth wear in general practice. It grades the exposed surface based upon the percentage of the tooth surface affected. A score of 0−3 is given for each sextant (for the worst affected tooth), and a total BEWE score is given out of a maximum 18 (Figure 1).

It was designed to be similar to a BPE (Basic Periodontal Examination) and therefore familiar to dentists. In common with the BPE, not every surface needs to be recorded, but the most severely worn surface in each sextant should be scored (Figure 1). The sum score (in the above example 16 out of a total of 18) gives an overall representation of the tooth wear in the dentition. As the authors of the BEWE acknowledged, care must be taken with evaluating the total sum as the final measure. If severe, but localized wear is present in the upper anterior sextant, then this will present with an overall lower score and, under the current classification system, would not represent high risk despite the severe wear. A total wear score will also underestimate wear in a partially dentate arch. A useful method is to use both the maximum sextant score in conjunction with the total score in a risk assessment. Any mouth containing a score of 3 should be considered high risk, even if elsewhere in the mouth the scores are lower. This recognizes the distribution of tooth wear is often localized. A maximum score of 2 indicates moderate wear and a moderate risk, whereas a maximum BEWE sextant score of 1 indicates low or no risk. Table 1 indicates a proposed method of risk assessment based upon tooth wear that is already present.

| High Risk Characteristics | Medium Risk Characteristics (Amber) | Low Risk Characteristics (Green) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum BEWE Score in any Sextant | 3 | 2 | 1/0 |

| Total BEWE Score | 13 or greater | 7–13 depending on age | 6 or lower |

It is important to consider the age of the patient when risk assessing tooth wear. Physiological wear and tear is normal, and it would be unusual to see a sextant BEWE score of 0 on a patient over the age of 30. It would be equally unusual not to see several sextant scores of 2 in a patient over the age of 55. The defining factor in risk assessment should be the presence of a BEWE score of 3. This is a sign of advanced wear at any age and the underlying aetiology needs to be diagnosed and managed. It is important to recognize that the need for restorative intervention is not related to the BEWE score.

Summarizing the risk assessment

A thorough history and examination is essential to risk assess tooth wear. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics outlined according to high (red), medium (amber) or low (green) characteristics. Behaviours change and risk assessments should be repeated at regular intervals. Any positive behaviours can also be reinforced (Table 3).

| High Risk Characteristics | Medium Risk Characteristics (Amber) | Low Risk Characteristics (Green) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erosion | Gastric Reflux Symptoms on a weekly basis or poorly controlled GORD |

Infrequent GORD symptoms or well managed symptoms |

No history or symptoms of GORD |

| Attrition | Flattened teeth already present and active soft tissue signs/symptoms |

Currently showing soft tissue signs/symptoms of bruxism but wearing mouthguard | No history of parafunction with no intra-oral signs of parafunction |

| Abrasion | Gingival recession and exposed dentine combined with aggressive brushing and interdental habits (3+ brushing per day and the use of a high RDA toothpaste) | Gingival recession and exposed dentine but non-aggressive brushing and interdental routine |

Brushes twice a day with low abrasive toothpaste |

| Overall Risk Characterization for Erosive Tooth Wear | |

|---|---|

|

Red

|

Presence of one aetiological factor in the red category |

|

Amber

|

Presence of one aetiological factor in the amber category |

|

Green

|

No daily risk of any component |

Conclusion

A comprehensive risk assessment for erosive tooth wear can be recorded at any stage and is important for the prevention of future wear. If the underlying aetiological factors are addressed, there is evidence that tooth wear progression can reduce to physiological levels.29 Active prevention methods such as effective preventive advice, fluoride measures and mouthguards should be a continuous intervention. Restorative intervention starts patients on a lifelong treatment journey and should be undertaken with caution and care. Improved understanding of their progression through active monitoring for a period greater than 6 months will assist in the diagnosis. Monitoring patients determining the activity of the aetiological factors and risk assessing is not supervised neglect and may lead to an improved diagnosis.