Article

Tooth wear is a common presentation to dentists and a frequent referral to consultant clinics in hospitals. The presentation can be localized or generalized. Thirty years ago, treatment consisted of conventional crowns, which could be a full-mouth reconstruction at an increased occlusal vertical dimension (OVD). Severe tooth wear was treated with overdentures. Such treatment was time consuming and had significant financial and biological costs. The patient was also committed to onerous long-term maintenance if the work was to be successful.

At this time, I provided a diagnostic and treatment planning service to dentists on new patient consultant clinics. Approximately five to six out of 10 patients attending presented with some form of tooth wear. Health authority guidelines dictated that high priority patients (cancer, trauma and developmental defects) had to be taken on for treatment, leaving about one in 10 patients being eligible for treatment by postgraduates. So, the bulk of patients commonly presenting to dentists with severe tooth wear had to be returned with a suggested treatment plan. Feedback from dentists about these clinics was always good, but I was sceptical about whether the work was undertaken or how successful it would prove to be. The NHS contract for dentists has never been sympathetic to providing this type of work and is more difficult to work with today. A simpler approach that most dentists could provide had to be developed.

Composite materials had significantly improved in the early 1990s and there was a move from older macrofill or microfill composites to hybrid materials with improved properties. At the same time, dentine bonding was becoming more predictable, and posterior composites were becoming the treatment of choice for small or medium-sized restorations. Treatment of tooth wear with composite was in its infancy.1 The common clinical challenge was establishing interocclusal space for restorations as usually there had been compensatory eruption of the teeth during the tooth wear.

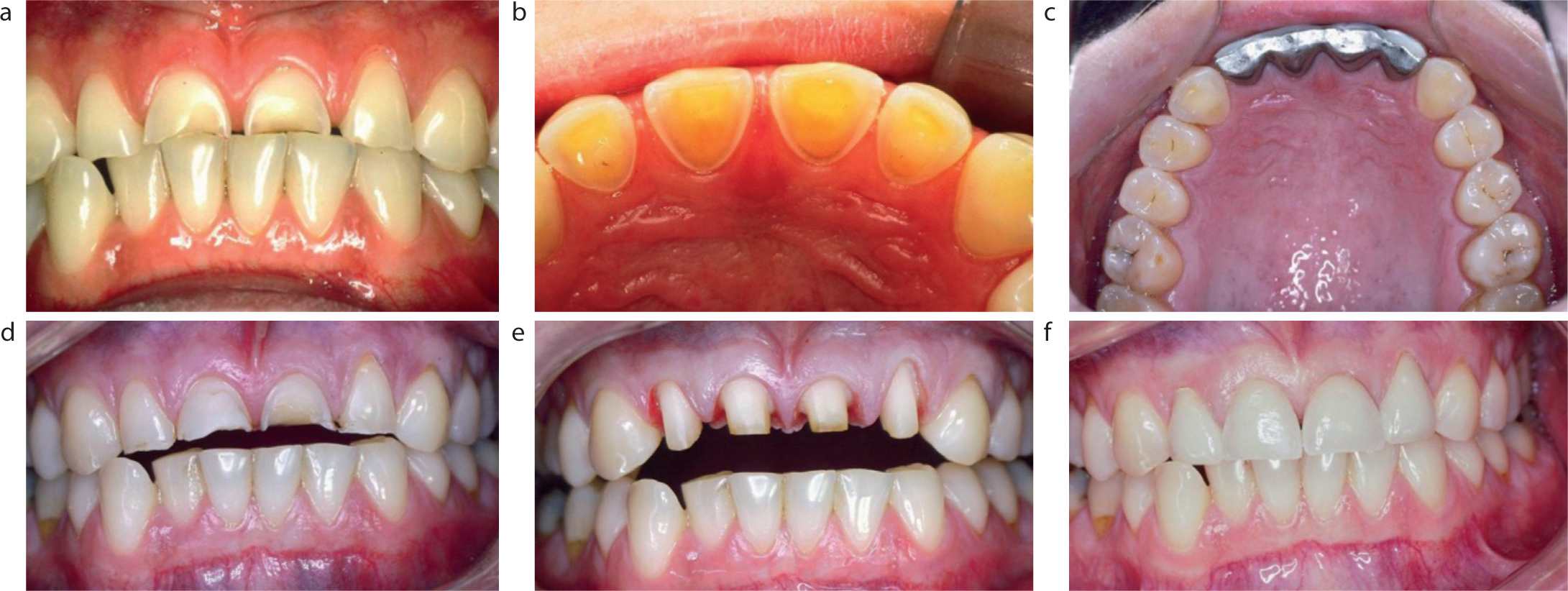

My hospital department has always had a strong interest in occlusion and had gained a reputation for dealing with unusual malocclusions. The use of Dahl appliances2 had been fully embraced with common use of anterior or posterior metal bite planes.3 Patient compliance had been overcome by cementing these appliances onto the teeth, but attempts at improving the appearance were poor. Invariably, once the interocclusal space had been generated the worn teeth were crowned with conventional crowns (Figure 1). As a side effect of this treatment, all resin-bonded bridges were cemented in ‘high’, and the occlusion left to settle after a few months. In this way, occlusal reduction of supporting or opposing teeth was obviated. This type of work remained in the hospital for many years.

I discussed how composite restorations could be used as a Dahl appliance with my fellow senior registrar, Dr Ulpee Darbar, in our office that the registrars shared. In this way, the appearance would be greatly improved and compliance for patients made easier. We also wondered how long the restorations would last. Discussions with our consultants and trainers, Derrick Setchell and Richard Ibbetson, were met with considerable scepticism. ‘They will never last’ was a reasonable concern. Nevertheless, they were broadminded enough to allow us to carry out a pilot study with 16 patients. The first patient treated in this way is illustrated in the original paper,4 which is reproduced in full in the following pages.

The pilot study was completed over 12 months and presented at the International Association of Dental Research (IADR) in San Francisco in 1996.5 The presentation was initially met with silence and then with incredulity. There were comments of ‘You can't do that!’ A supportive and perceptive chairman made an analogy to the use of orthodontic bite planes, which was helpful. I had a similar experience 2 years later at the Nice IADR in 1998, when a larger patient group was presented with 30 months' follow-up.6,7 I was grateful to Alex Milosevic and Peter Briggs for their support having carried out similar studies with equally good results.8,9 This technique has subsequently been adopted in many parts of the world,10 but there is still scepticism in the USA.11

It seems that the restorations can last for about 7 years before repair or replacement is carried out, and can continue for 10 years or more.12 Many different techniques have now been described, including injection moulding, which need a varying amount of laboratory support. Common to all techniques will be attention to clinical detail so that the survival of the material and bonding to teeth can be maximized.

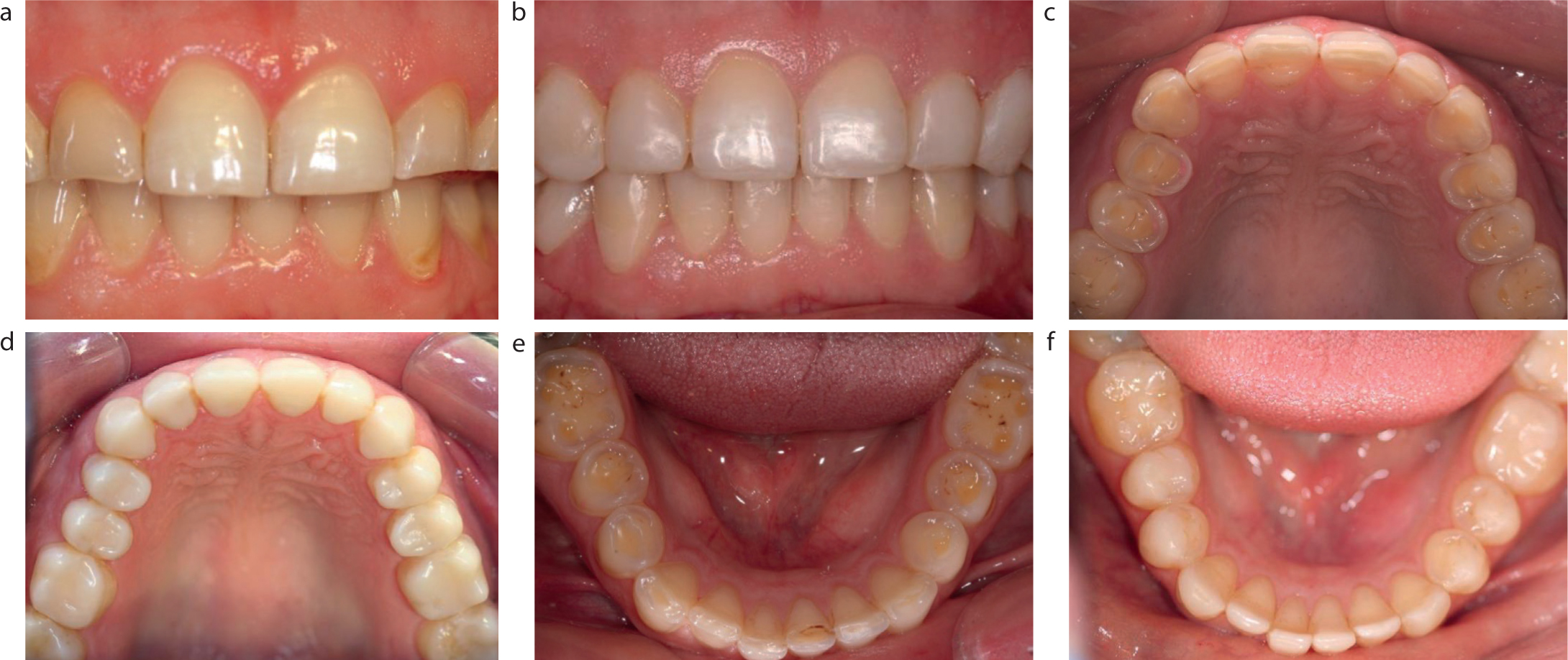

It would appear attractive to extend the use of composite restorations to treating generalized wear with full-mouth reconstructions. This has been described in case reports, with demonstrations of excellent work without damaging the teeth, but long-term follow-up is lacking at present (Figure 2).13 Developments continue and, in time, this approach may prove to be successful. Heavily restored teeth may still be best treated with conventional crowns or onlays.

The ‘Composite Dahl’, as it is now known, has benefited many patients and provided a cost-effective way of managing localized anterior tooth wear.