Abstract

This article considers the importance of current orthodontic practice in retention and stability when considering anterior tooth alignment.

From Volume 41, Issue 4, May 2014 | Pages 306-312

This article considers the importance of current orthodontic practice in retention and stability when considering anterior tooth alignment.

Anterior tooth alignment seems to be a treatment option preferred by dentists as the non-invasive alternative to destructive tooth preparation for adult patients. Although, from a biological perspective, this may be an ideal way to provide a conservative approach, it is open to controversy, particularly if the treatment time is considerably shortened. The key issues being related to compromised treatment goals, informed consent, clinical consequences of retreatment and long-term stability.1

Anterior tooth alignment is a feasible treatment option for adult patients and constitutes one of the many possible solutions after a thorough orthodontic and aesthetic assessment. The assessment should consist of understanding the patient's chief complaint, performing a thorough evaluation with relevant diagnostic analysis which will allow for the formulation of a problem list from which treatment goals and solutions can be devised. A joint consultation with the patient, restorative dentist and the inclusion of other specialties, if necessary, at the outset may prove invaluable and is to be recommended.

When considering different treatment options, the clinician must be able to explain how the malocclusion affects the patient aesthetically, functionally and biologically. Treatments advocating a long-term improvement in the prognosis of teeth and the stomatognathic system will inevitably be more cost-effective in the long run.

Therefore, case selection for anterior tooth alignment requires a full disclosure of treatment options, with advantages and disadvantages of each treatment plan, before the patient can make an informed and educated decision.

When the decision to embark on an anterior tooth alignment case is made, consideration needs be taken on both the occlusal stability and the retention protocol. This should essentially be at the treatment planning phase and utilize an evidence-based approach to comprehensive orthodontic treatment regarding retention and stability.

A good starting point is by reviewing the findings from the Cochrane Library on ‘Retention procedures for stabilizing tooth position after treatment with orthodontic braces’.2 The study compared Hawley retainers, clear vacuum-formed retainers and fixed retainers, along with the use of the circumferential supercrestal fibrotomy procedure. The review states that there is a lack of robust evidence on which to base clinical practice owing to the inclusion of only five randomly controlled trials in the study. However, the review demonstrates the benchmark for the basis of further studies to improve research and understanding in this field. The answers or lack of answers derived from evidence-based research should be considered with other influences, such as cognitive or political factors, when setting up good practice.3

One of the most useful and easily accessible papers on retention protocol, which supersedes any recommendation made by opinion, is The Royal College of Surgeons' Clinical Guidelines: Orthodontic Retention.4 The approach of the paper is based on sound evidence and looks at occlusion and other factors (such as rotations, spacing, periodontal health, root resorption, lower incisor alignment and position) which may modify retention protocol. This allows the clinician to think of bespoke retention protocols rather than habitual prescription for his/her patient and ask the question: What practical lessons can we learn about retention from comprehensive orthodontics that can help the stability of anterior tooth alignment cases?

To answer this we need to agree on the definition of retention. One of the most complete definitions of retention found in the literature is by Graber et al5 who define retention as ‘… the holding of teeth in optimal aesthetic and functional position.’ There are two factors which affect retention; one being the teeth trying to relapse to their original position and the other is the continuous ageing change of the adult dentition. Therefore, retention protocol needs to take both factors into account by the provision of retainers and by good maintenance of the overall dentition on a long-term basis. The following recommendations are based on opinion, experience and important theories widely accepted in orthodontic literature.

Anterior tooth movement, whether it is for mild crowding or spacing, will cause stress and deformation of the attaching fibres in the periodontium. In particular, the collagen fibres of the periodontal ligament fibres and the elastic dento-gingival and inter-dental fibres. Reitan6 demonstrated that it takes up to 8 months for the fibres to remodel once the teeth have been held in the corrected position. Therefore, a strict retention protocol needs to be in place immediately after completion of orthodontic treatment to avoid relapse.

de Freitas et al7 demonstrated, in a study of Class I malocclusions, that the quality of the finished occlusion achieved after orthodontic treatment had an effect on post-treatment relapse. Good orthodontic finishing was directly linked to better long-term stability. Anterior tooth alignment cannot guarantee good occlusal finishing of the whole occlusion; however, attention to case selection for anterior alignment cases reduces the need to compromise a result. Choosing cases with stable intercuspated buccal segments, normal overbite and overjet values with correct functional occlusion is a good start point.

The neutral zone as described by Proffit8 and Dawson9 is based on the principle that teeth will not stay stable where muscles and soft tissues do not want them to be. The neutral zone is the area of balance between the tongue on one side and the buccinators and lips on the other side. Therefore, the strength and position of the peri-oral muscles and tongue will dictate the position and inclination of the anterior teeth. Any large orthodontic movements of the anterior teeth especially associated with an increased overjet may put the teeth in an area of increased instability.

The classic studies at the University of Washington by Little et al10 concluded that the orthodontist should not assume that stability will occur after orthodontic treatment. Hence, the only way to ensure continued satisfactory alignment post-treatment is retention for life.11

Frustratingly, when orthodontic relapse does occur, it is most frequently seen in the mandibular anterior segment during the post-retention period.12 The main reason for this development of relapse or crowding is due to the decrease in the dental arch width and length over time; this has been found to occur in treated and untreated subjects.13 Dental maturation changes are inevitable14 and this fact only further confirms the need for long-term retention to improve stability for adult patients.

Blake and Bibby15 reviewed the orthodontic literature on long-term retention and evaluated the stability of various treatment modalities. Their recommendations, related to determining the final tooth position, are based on well documented studies and listed below:

The true value of all pre-restorative orthodontics is to reduce the amount of invasive dentistry required and increase the longevity of any restorative work planned. The success of alignment and additive bonding as a minimally invasive approach will depend on long-term stability. If the anterior teeth relapse, there could be a change in the functional occlusion and this could result in the failure of the additive bonding and an unhappy and aggrieved patient. Retreatment will have both financial and biological implications.

Additive bonding should be used to enhance the aesthetic result and, where possible, the functional occlusion. This, combined with a correct retention programme, will increase the outcome of success from an orthodontic and restorative perspective. This will be demonstrated in the case report that follows.

The provision of the type of retainers prescribed to a patient is bespoke for each individual case as recommended in the RCS guidelines mentioned earlier.4 The initial malocclusion and the state of the overall dentition also need to be taken into account when creating a retention protocol. The main types of retainers used are fixed, such as the bonded retainer, or removable, such as the Hawley, Begg or Essix retainer. Experience has shown that the provision of two retainers per arch reduces the dependency on relying on one retainer, which may get damaged or lost over a period of time.16

A recent study has evaluated the difference in the clinical effectiveness of either using an Essix or a Begg retainer17 and concluded that they are both as effective as each other. However, there was a better patient acceptance of the Essix retainer in terms of appearance. Another comparative study18,19 compared the amount of relapse after the use of the Essix retainer and the Hawley retainer; both performed in a similar manner of clinical effectiveness.

However, there are specific indications when a fixed retainer has been deemed to be more beneficial than a removable retainer.20 These are listed below:

Many of the above scenarios are common in anterior tooth alignment, therefore it is important for dentists to have this retainer option available for their patients. The technique for the placement of the bonded retainer needs to be perfected, as failure rates can be associated with the skill of the operator.21,22

As well as the provision of retainers, patients should be supervised for at least six months to help guide them into their retention programme. This should be combined with patient education and written consent to help consolidate the retention protocol.

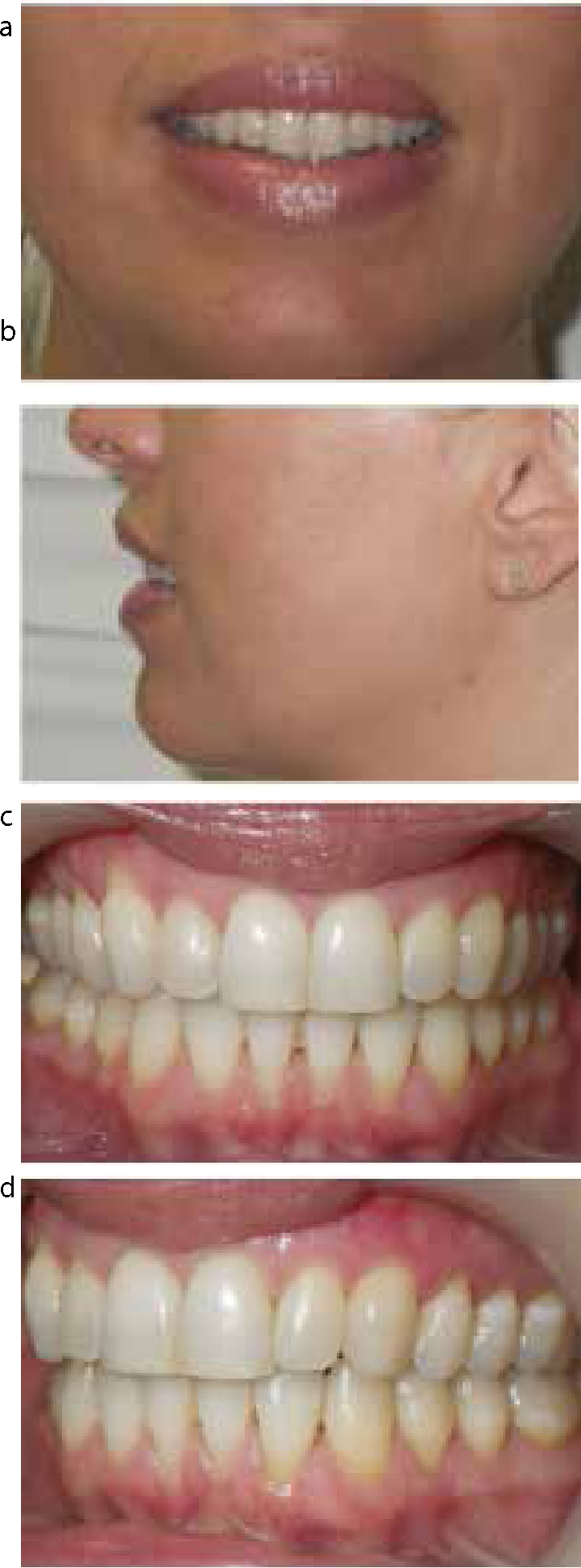

A fit and healthy 35-year-old woman was referred to the orthodontist from her GDP. The patient had initially asked her GDP for a ‘Hollywood smile’ with veneers to improve her smile and anterior incisor alignment. The GDP recommended that she sought an orthodontic opinion for an ortho-restorative approach with minimally invasive dentistry.

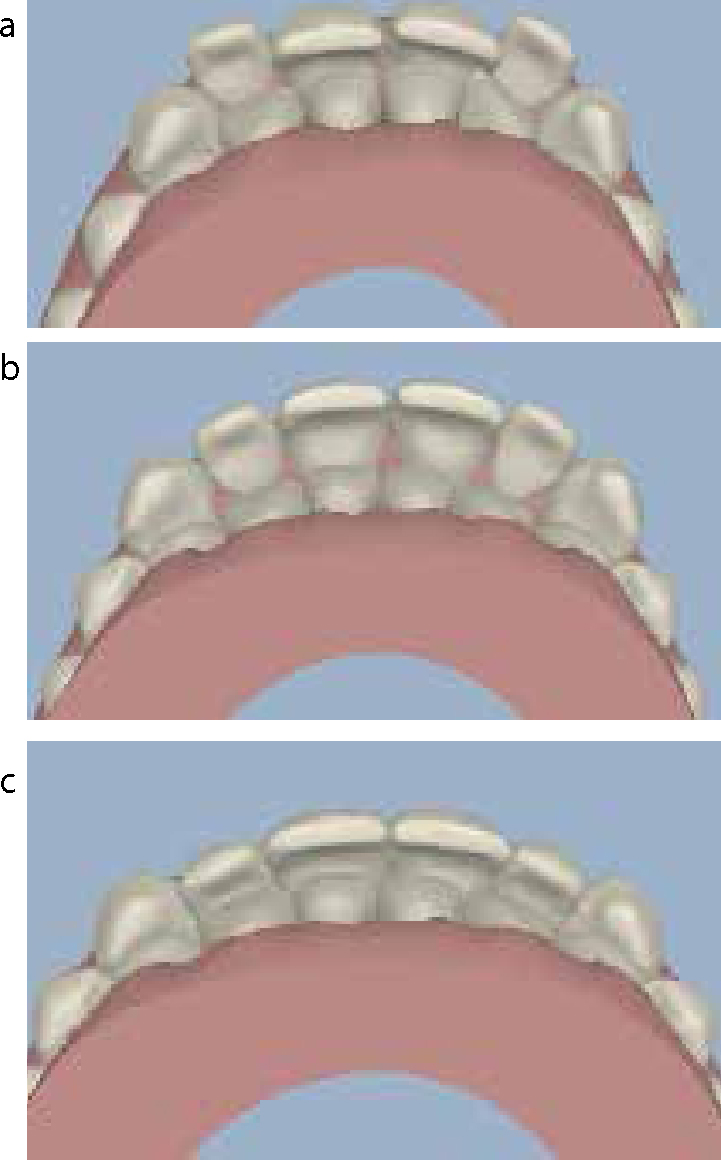

A full aesthetic and orthodontic assessment was carried out and a medium lip line was noted which masked the recession on the upper right canine tooth. The patient presented with a Class II division 2 incisor relationship on a mild Class II skeletal base with a high angle tendency. The overjet was 2 mm and overbite decreased but complete. The buccal molar segments were tightly inter-cuspated in a Class II occlusion on both sides. The canines were also in a Class II relation and involved in canine guidance on the left side and group function on the right. There was moderate crowding in the upper arch and mild crowding in the lower. There was a tooth size discrepancy associated with small upper laterals which were involved in a lip catch and drifting over time. The position of these lateral incisors contributed to the smile arc alignment that could benefit from improvement (Figure 1).

Four treatment plans were presented and explained to the patient with the referring GDP. These took into account the options of extraction versus non extraction as well as correction or acceptance of the tooth size discrepancy. Three types of orthodontic appliances (ceramic braces, lingual braces and clear aligners) had been offered to the patient. The choice of Invisalign fulfilled the patient's aesthetic needs and met the orthodontist's needs in terms of movements required, which included rotation correction, overbite and torque control. The use of the Clincheck software was a useful tool to communicate and relay information.

The treatment time was 12 months, requiring 23 aligners in the upper and 12 in the lower. Power ridges were used for torque control of the upper central incisors. Refinement aligners were used for detailing the final position of the upper laterals (Figure 5: final orthodontic result and corresponding Clincheck showing the pre-restorative position of the incisors which could now benefit from minimal intervention dentistry with additive composite bonding).

The final post-orthodontic and restorative result has achieved the treatment goals set earlier. A good aesthetic result has been achieved with function and stability kept in mind from the start (Figure 6).

Anterior tooth alignment primarily aims at improving dentofacial aesthetics; however, it should not compromise stomatognathic function or place teeth in a position of instability. For this reason, case selection is an important factor associated with anterior tooth alignment cases. The overall assessment, treatment planning and retention protocol should be as vigilant as that set for comprehensive orthodontic and restorative treatment in order to ensure long-term stability.