References

The orthodontic/paediatric interface part 1

From Volume 45, Issue 8, September 2018 | Pages 760-772

Article

Paediatric dentists and orthodontists collaborate in treatment planning and care provision for many paediatric patients. A good working relationship, free-flowing communication and continual sharing of information between the paediatric dentist and orthodontist will ensure that treatment is provided in the most efficient and effective manner. This multidisciplinary approach is encouraged in all areas of healthcare and is not a new concept. In 1979, the Royal Commission of the NHS stated that ‘we are in no doubt that it is in the patients’ interests for multidisciplinary team working to be encouraged.’1

When the paediatric dentist and orthodontist are located at the same site, communication between them is much easier and more efficient than when they are separate. In secondary care, many members of a multidisciplinary team may be able to be present at a single appointment. This can enable them to discuss the intricacies of a treatment plan with the patient present. For general dentists, there is often the need for an external referral to an orthodontist in primary or secondary care if orthodontic advice or treatment is needed. This process takes time and can delay the commencement of treatment.

Orthodontic/paediatric collaboration is required in a broad spectrum of cases. This article looks at some of the most common situations where orthodontic/paediatric collaboration is often needed. There are other topics where this collaboration occurs that are beyond the scope of this article.

Extraction of primary teeth

Prior to enforced extraction of a primary tooth, the following recommendations should be considered:

Extraction of primary incisors

Extraction of primary canines and first molars

Extraction of primary second molars

Prolonged retention of primary teeth

Prolonged retention of primary teeth can occur for a number of reasons. The most common cause of retention of primary teeth is absence of the permanent successor. In these cases, it is prudent to refer the patient to an orthodontist to determine the most suitable treatment options. In some cases, it may be beneficial to retain this primary tooth into adulthood.

Primary teeth can also be retained as a result of other causes, such as genetic or syndromal factors, trauma, ectopic eruption of the permanent successor, infra-occlusion, ankylosis, crowding or the presence of obstructions such as supernumeraries. General dentists should monitor eruption of the permanent dentition and investigate further, with radiographic examination, if a permanent tooth has not erupted within 6 months of the contra-lateral tooth. A referral to an orthodontist or paediatric dentist may be warranted, if a primary tooth is over-retained, as it can cause a deflection in the eruption path of the permanent successor. This, in turn, can result in crowding, crossbite and displacement.

Space maintainers

Space maintenance is the preservation of a space in the primary or permanent dentition. In the primary dentition, space maintainers can be used to prevent a malocclusion of the permanent teeth. In the permanent dentition, they can be used to preserve a space from a tooth lost due to trauma or caries or congenitally missing teeth.

Management

A natural tooth is the best space maintainer and primary molars should be preserved if possible. The decision to fit a space maintainer after enforced extraction must be arrived at by balancing the occlusal disturbance that may result if one is not used against the plaque accumulation and caries that the appliance may cause. Poor oral hygiene is a contra-indication.

Space maintenance is most valuable in two situations:

Table 1 describes different types of space maintainers.

| A Natural Tooth | Removable Space Maintainers | Fixed Space Maintainers |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1 shows a case where a loop space maintainer was fitted to the LR6 to maintain the space created by removal of the LRE.

Enforced extraction of poor quality first permanent molars

Children may present with a developing dentition affected by one or more first permanent molars of poor prognosis, necessitating their enforced extraction. This is due to the susceptibility of first permanent molars to caries in childhood and their association with molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH). In the right circumstances, first permanent molar extraction can be followed by successful eruption of the second permanent molar to provide a suitable replacement, and ultimately third molar eruption, to complete the molar dentition. The elective extraction of first permanent molars with questionable long-term prognosis should be considered when planning enforced extraction. These treatment planning decisions should ideally be made following input from both the general or paediatric dentist and the orthodontist, although this may not always be possible.3 The management of the extraction of first permanent molars of poor prognosis is described in Table 2.

|

Balancing Extractions

|

Compensating Extractions

|

| Routine balancing extraction of a sound first permanent molar to preserve a dental centreline is not recommended. | Lower first permanent molar extraction: |

| Timing of the first permanent molar extractions: Ideally, a first permanent molar would be extracted and be replaced by a second permanent molar | |

| Timing of upper molar extractions | Timing of lower molar extractions |

|

|

|

Balancing and compensating extractions

The practice of compensating and balancing the extraction of first permanent molars aims to preserve occlusal relationships and arch symmetry within the developing dentition.

A number of factors can influence whether a first permanent molar is recommended for either a balancing or compensating extraction:

Figure 2 demonstrates a case with heavily restored first permanent molars.

The paediatric or general dentist must consider the child's future need/desire for orthodontic treatment. However, it may not be practicable to seek a specialist orthodontic opinion prior to carrying out the necessary dental treatment. In these cases, the dentist should proceed as follows:

Non-nutritive sucking habits

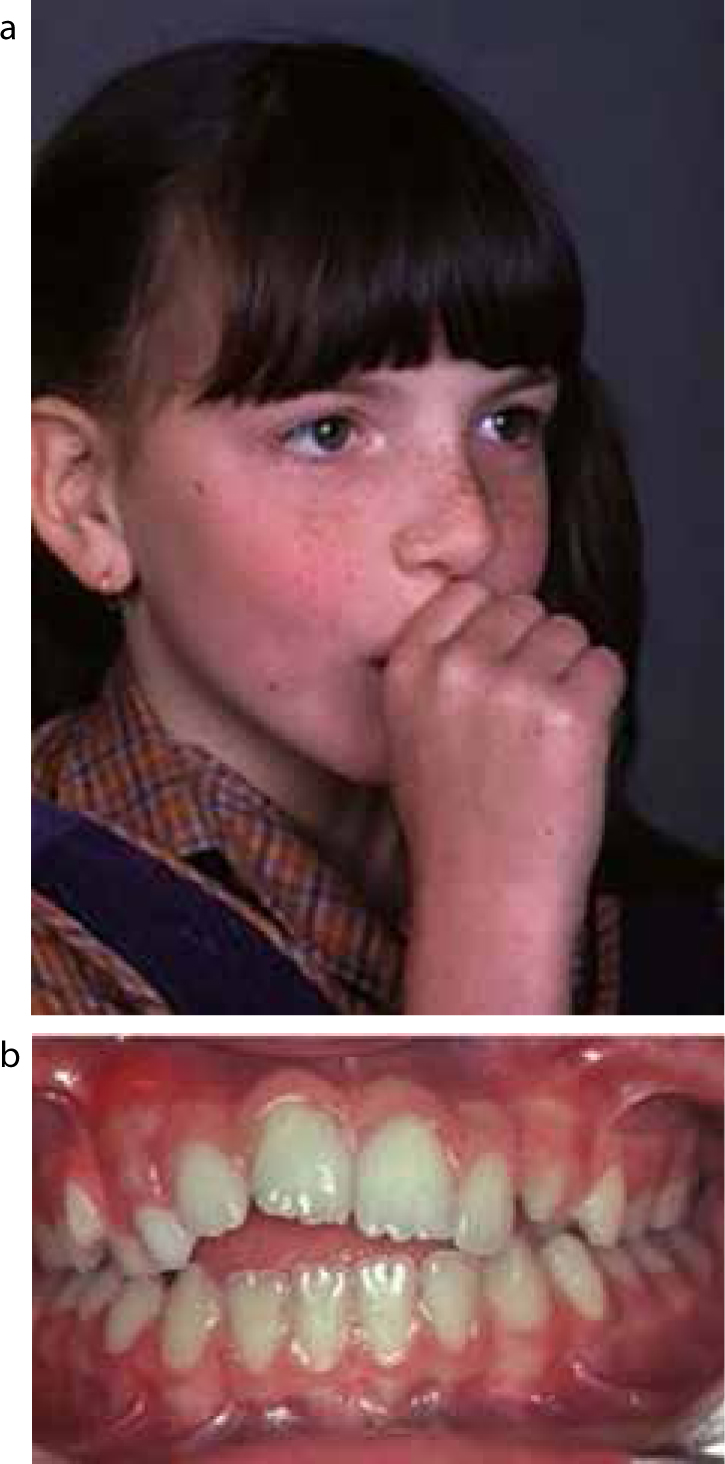

Non-nutritive sucking habits occur when a child regularly sucks on objects such as pacifiers, digits, toys or blankets.4 This is a normal behaviour for infants, but can cause malocclusions if the habit persists. The malocclusion will differ according to the type, frequency and duration of the habit. An anterior open bite is common and is usually symmetrical in dummy suckers and asymmetric in digit suckers. The anterior open bite is caused by interference with normal eruption of the incisors along with excessive eruption of the posterior teeth. Figures 3a and 3b show extra-oral and intra-oral views of a patient with a thumb-sucking habit. An asymmetric open bite is seen in this case.

Posterior crossbites can occur due to the lower position of the tongue which is out of contact with the upper arch.5 Non-nutritive sucking habits can also cause an increased overjet, which in turn can be linked to an increased risk of trauma to the maxillary incisors.

Cessation of these habits can be difficult. Some children respond through reward, but others need a strong deterrent. The application of bitter tasting chemicals to a pacifier or to the digit only works in limited cases. Sometimes the withdrawal of a pacifier can lead to replacement with a digit. The crucial time for elimination of a sucking habit is as the permanent incisors erupt. If the habit persists to this stage, further intervention to aid cessation may be needed. The evidence for both orthodontic and psychological interventions for the cessation of non-nutritive sucking habits is low quality, but has shown that both orthodontic appliances (palatal arch and palatal crib) and psychological interventions (including positive and negative reinforcement) are effective at improving sucking cessation in children.6

Ectopic eruption of first permanent molars

Ectopic eruption of a first permanent molar occurs when the tooth follows an abnormal eruption pathway. The first permanent molar's mesial eruption causes it to contact the distal surface of the second primary molar tooth and cause resorption of this tooth to varying degrees of severity. Early treatment is essential to move the ectopically erupting molar away from the tooth it is resorbing. This allows the permanent molar to erupt into a normal position, whilst maintaining a normal arch circumference. If left untreated, the permanent molar can erupt with rotation, mesial tipping and poor occlusion.7

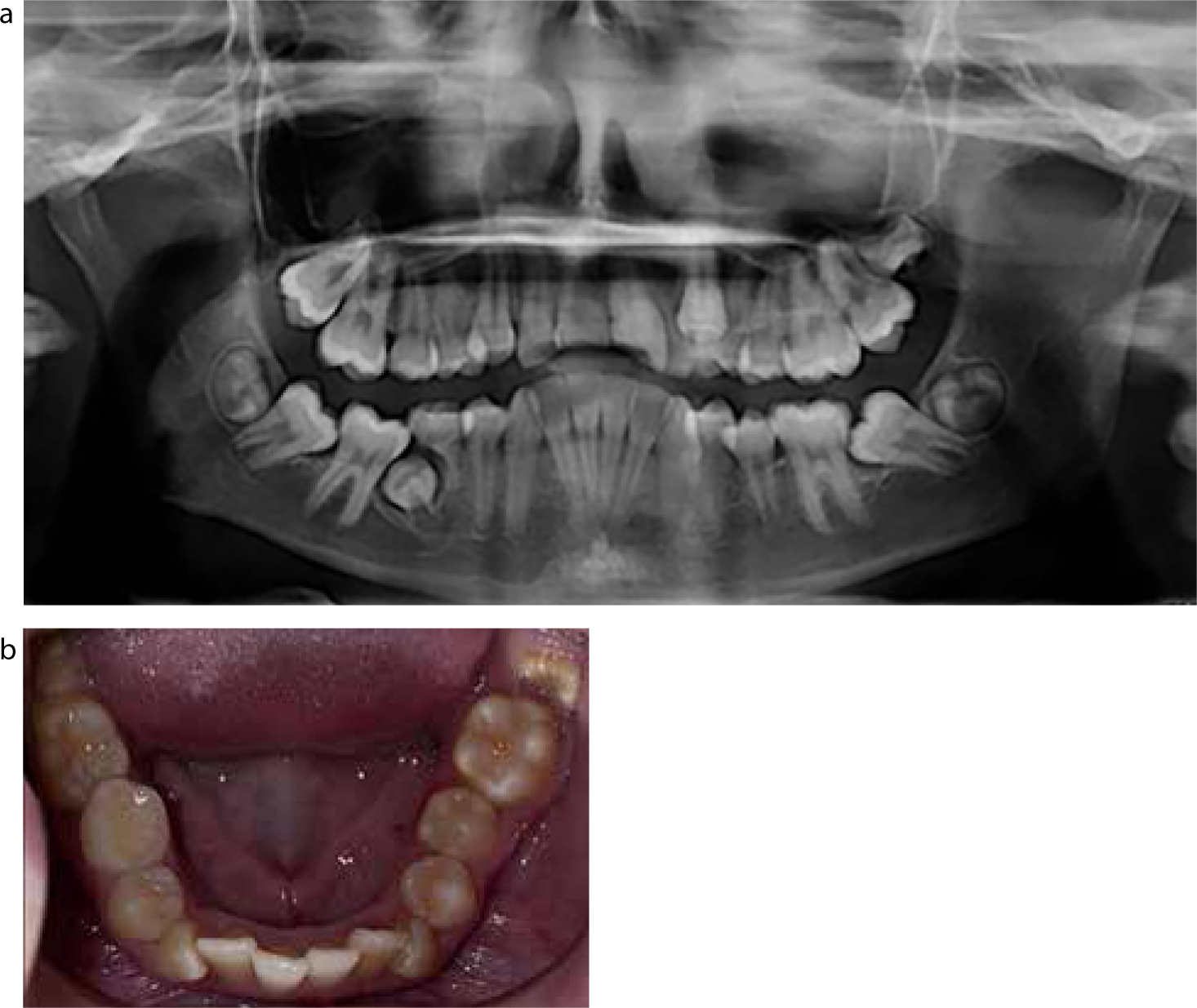

Ectopic eruption is usually diagnosed on radiographic examination carried out between 5 and 7 years of age. The first permanent molar would appear impacted onto the crown or distal root of the second primary molar tooth and atypical resorption may also be evident.8Table 3 shows the classification of ectopic molars based on type and grade. Figures 4a and 4b show a LR6 which is impacted and causing resorption of the LRE and impeding eruption of the LR5.

| Type | Degree (based on the magnitude of resorption of the second primary molar) |

|

|

|

Causes

The cause of ectopic first permanent molar eruption is thought to be multifactorial. Some of the factors that can be involved are:9

Ectopic eruption of first permanent molars is also more common in children with cleft lip and palate and in those with a family history.10

The different management modalities for ectopic first permanent molars are described in Table 4.

| Monitoring | Separation | Active Appliance | Extraction of the Second Primary Molar and Appliance Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Impacted canines

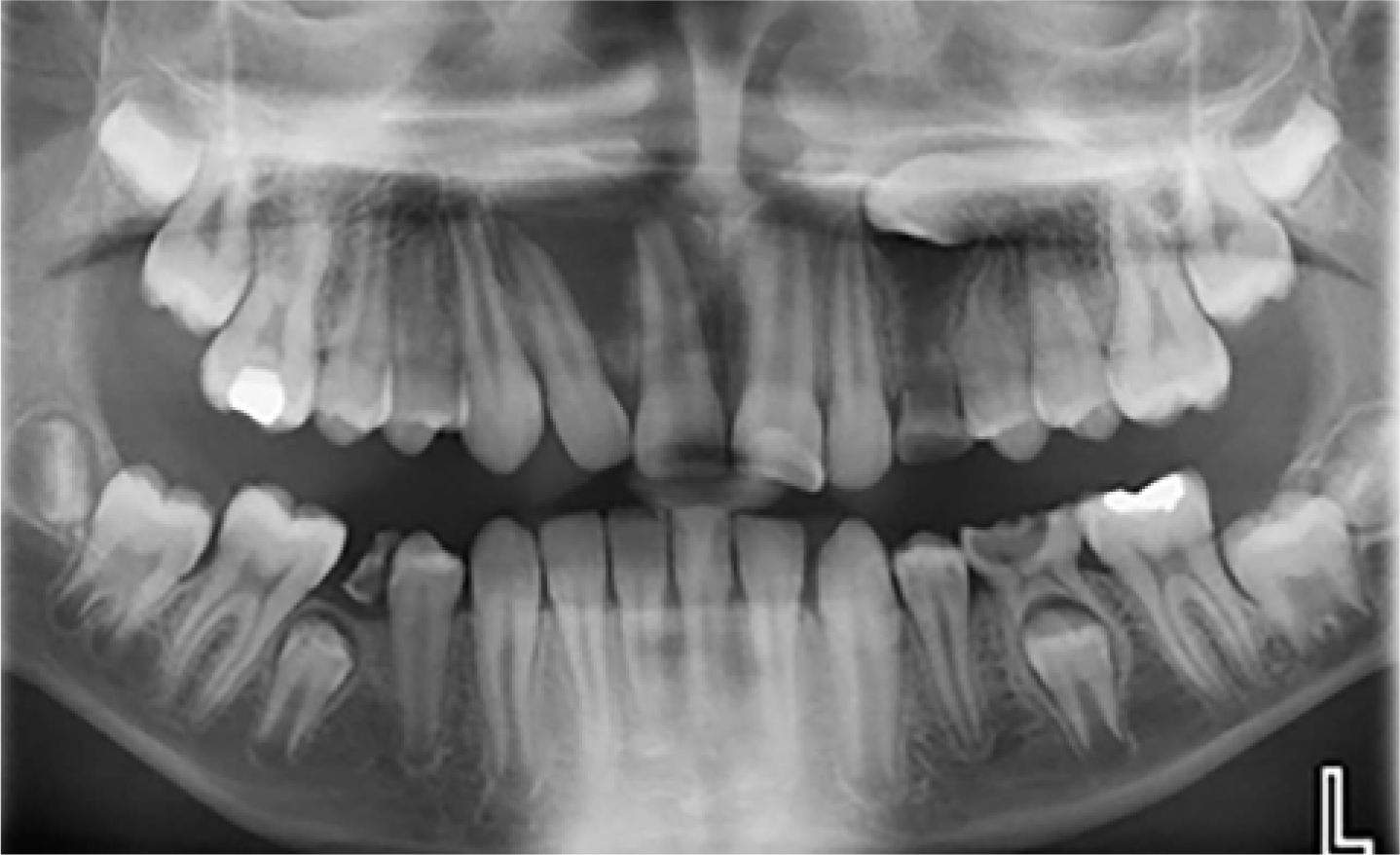

Following the third molar, the maxillary canine is the next most common tooth to be impacted. Palatal ectopic canines occur much more frequently than those positioned buccally. Palatal impactions have been reported as high as 92.6%.11 The paediatric and general dentist must palpate for unerupted maxillary canines as part of their examination of every patient from 8 years of age. Maxillary canines following a normal eruption are palpable in the buccal sulcus between 10 and 11 years of age.12 Maxillary canines erupting after 12.3 years of age in a girl and 13.1 years of age in a boy are considered late.13 Impacted maxillary canines can cause resorption of the adjacent incisor roots and so early identification and treatment is essential. Figure 5 shows an impacted UL3. This tooth is ectopic and is lying horizontally close to the apices of the premolar teeth.

Causes of impacted canines

The aetiology is unclear, but some causes are thought to be:14

The management of an impacted canine is described in Table 5.

| Interceptive Treatment with Extraction of Primary Canine | Surgical Exposure and Orthodontic Alignment | Surgical Removal of the Palatally Ectopic Maxillary Canine | Transplantation | Leave or Observe the Canine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Management of unerupted maxillary incisors

The absence or delayed eruption of a maxillary incisor can be a real cause for concern for a child and his/her parents. Missing maxillary incisors are conspicuous and can have an adverse effect on the child's self-esteem and interaction with others. A study of Jordanian schoolchildren found that teeth were the most likely feature targeted for bullying. In particular, the spacing of teeth, missing teeth, shape and colour of teeth.15

The delayed eruption of a maxillary incisor should be investigated when:

| Children up to Nine Years with Incomplete Root Development of Permanent Incisor | Children above Nine years with Complete or Nearly Complete Apex | If Permanent Incisor is Impacted | Children Referred Late (over 10 years) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Correction of crossbites

A crossbite is a condition where one or more teeth may be abnormally positioned buccally or lingually with reference to the opposing tooth or teeth in centric occlusion.

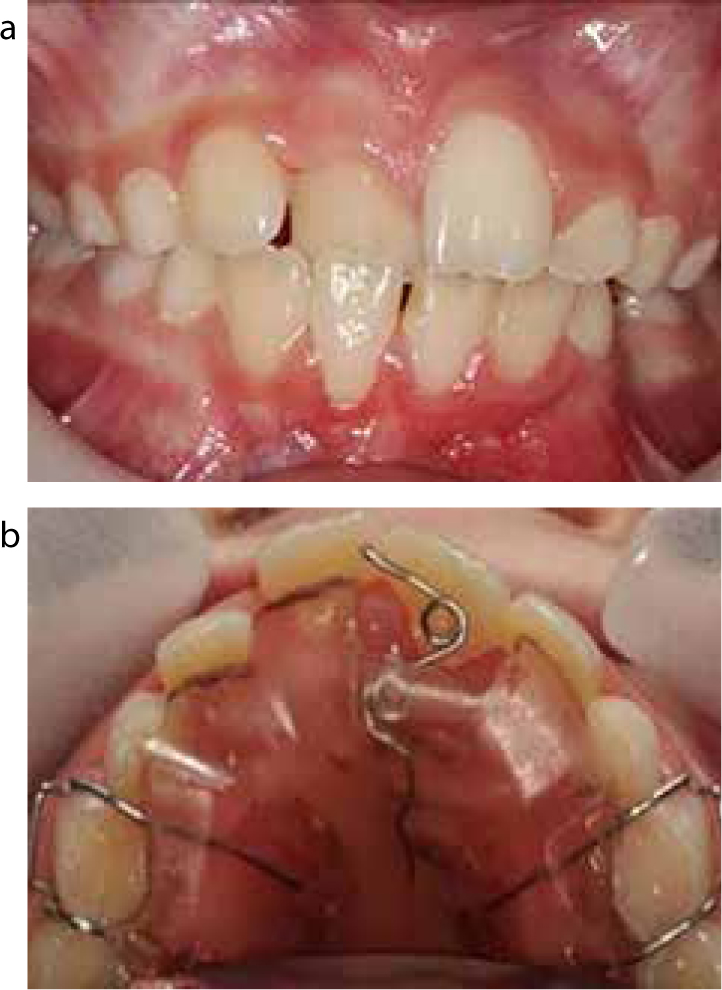

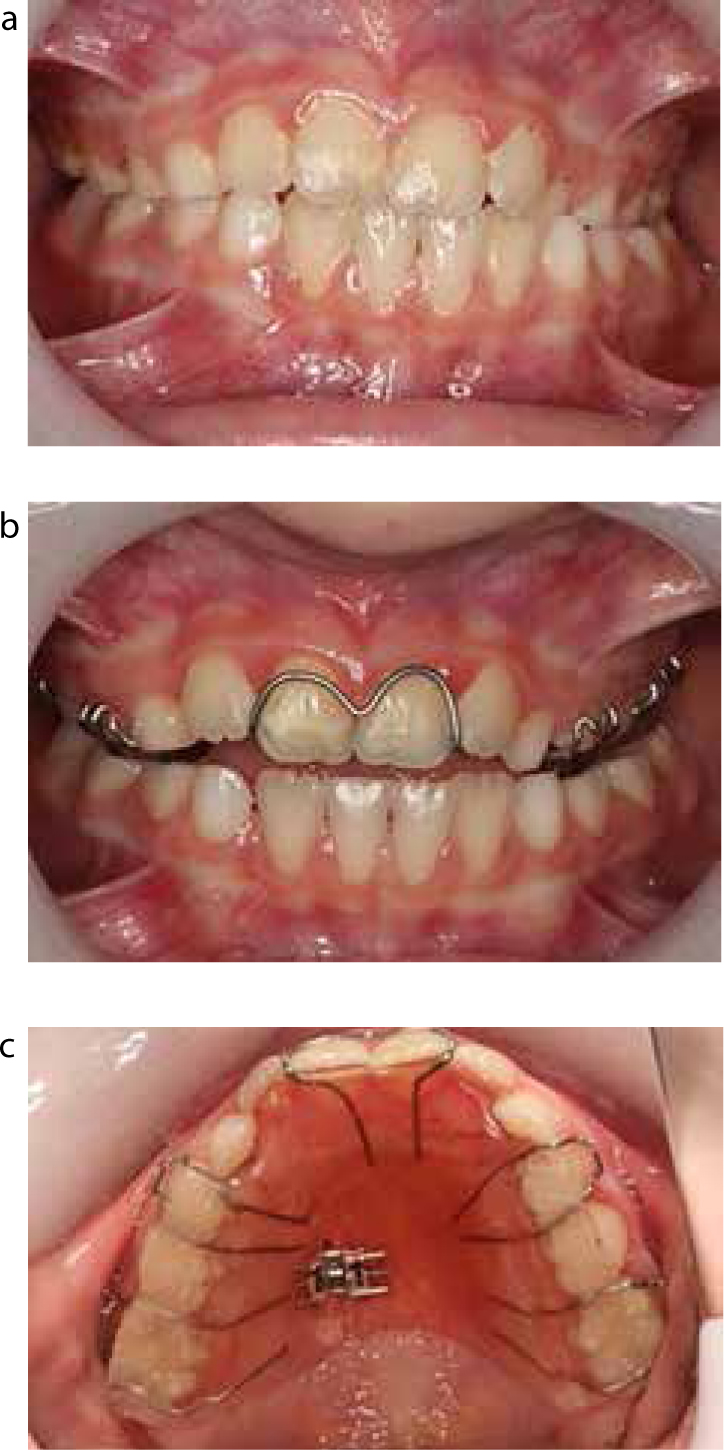

Anterior crossbite is the term used when the maxillary anterior teeth are in a palatal position relative to the mandibular anterior teeth. Anterior crossbites can be either dental or skeletal in origin. Anterior dental crossbites originate from the abnormal axial inclination of the maxillary anterior teeth. Anterior skeletal crossbites are associated with a skeletal problem, such as mandibular prognathism and midface deficiency.17Figure 7a shows an UR1 in anterior crossbite. Figure 7b shows the upper removable appliance that was prescribed, which incorporated a z-spring to procline the UR1 and a posterior bite plane to open up the bite.

Posterior crossbites occur when there is a crossbite involving a premolar, molar or a whole buccal segment. Posterior crossbites can be further subdivided into:

General dentists should refer to an orthodontist when they identify a patient with any of the following features:

The different treatment options for anterior and posterior crossbites are described in Table 7.

|

Anterior Dental Crossbite

|

Posterior Dental Crossbite

|

|

Treatment options:

|

Treatment options:

|

Figure 8a shows a case with a unilateral posterior buccal crossbite on the left side and molar incisor hypomineralization. Figures 8b and 8c show the upper removable appliance that was prescribed to correct the crossbite, which incorporated a split screw and a posterior bite plane.

Trauma

An increased overjet and inadequate lip support of the maxillary incisors have been found to be significant risk factors in traumatic dental injuries.18 The orthodontist will therefore see a large number of patients with a history of dental trauma.

The paediatric or general dentist and the orthodontist will need to work closely in cases with a history of trauma. The paediatric or general dentist must inform the orthodontist if a patient has had a previous incidence of dental trauma as these patients are at a higher risk of further dental traumatic injuries.19 The orthodontist may be involved in planning movement of traumatized teeth that have experienced a whole range of injuries.

Prevention

Early orthodontic treatment with functional appliances (involving two-phases of treatment between 7–11 years of age) for children with an increased overjet can reduce the risk of incisal trauma compared to one-phase orthodontic treatment in adolescents.20

Participation in both contact and non-contact sports has been shown to increase the risk of dental traumatic injury. Many studies show that the use of custom-made mouthguards can prevent such injuries.21 The paediatric or general dentist should consider prescribing a custom-made mouthguard for all of their patients who participate in sports, especially those with an increased overjet and incompetent lips. These mouthguards should still be worn during orthodontic therapy.

Management

Orthodontic treatment of traumatized teeth may be required to:

Special consideration needs to be made before carrying out orthodontic movement on a previously traumatized tooth. The patient with a previous history of dental trauma should be informed of the higher risk of pulp necrosis, root resorption and further episodes of trauma during orthodontic treatment.

Conclusion

Paediatric dentists and orthodontists work closely in a wide range of cases, as demonstrated in this paper. The orthodontist contributes to treatment planning and provision for patients presenting with issues ranging from simple crossbites to severe trauma. Combining the skills of the paediatric and orthodontic specialists will ensure the best management of these common problems.