Article

Glass ionomer cements (GICs) have been available for use by clinicians for almost 50 years.1 Their beneficial properties, such as adhesion to tooth substance, have long been recognized, but early materials suffered from brittleness, lack of translucency, poor wear resistance and solubility in oral fluids and therefore were not suitable for use in loadbearing situations in posterior teeth. New, improved variants of GICs have become available in recent decades which overcome some of these difficulties. Results of latest research indicate that, under in clinical situations, such as Class I cavities and Class II cavities with limited interproximal box width,1 new GIC variants may provide successful restorations and other, recent publications have demonstrated that they are more costeffective than resin composite materials in an equivalent clinical situation.2 It is therefore the purpose of this article to suggest technique tips which may optimise the performance, in loadbearing situations in posterior teeth, of latest reinforced GICs and the glass hybrid materials which have developed from the reinforced GICs.

Cavity design

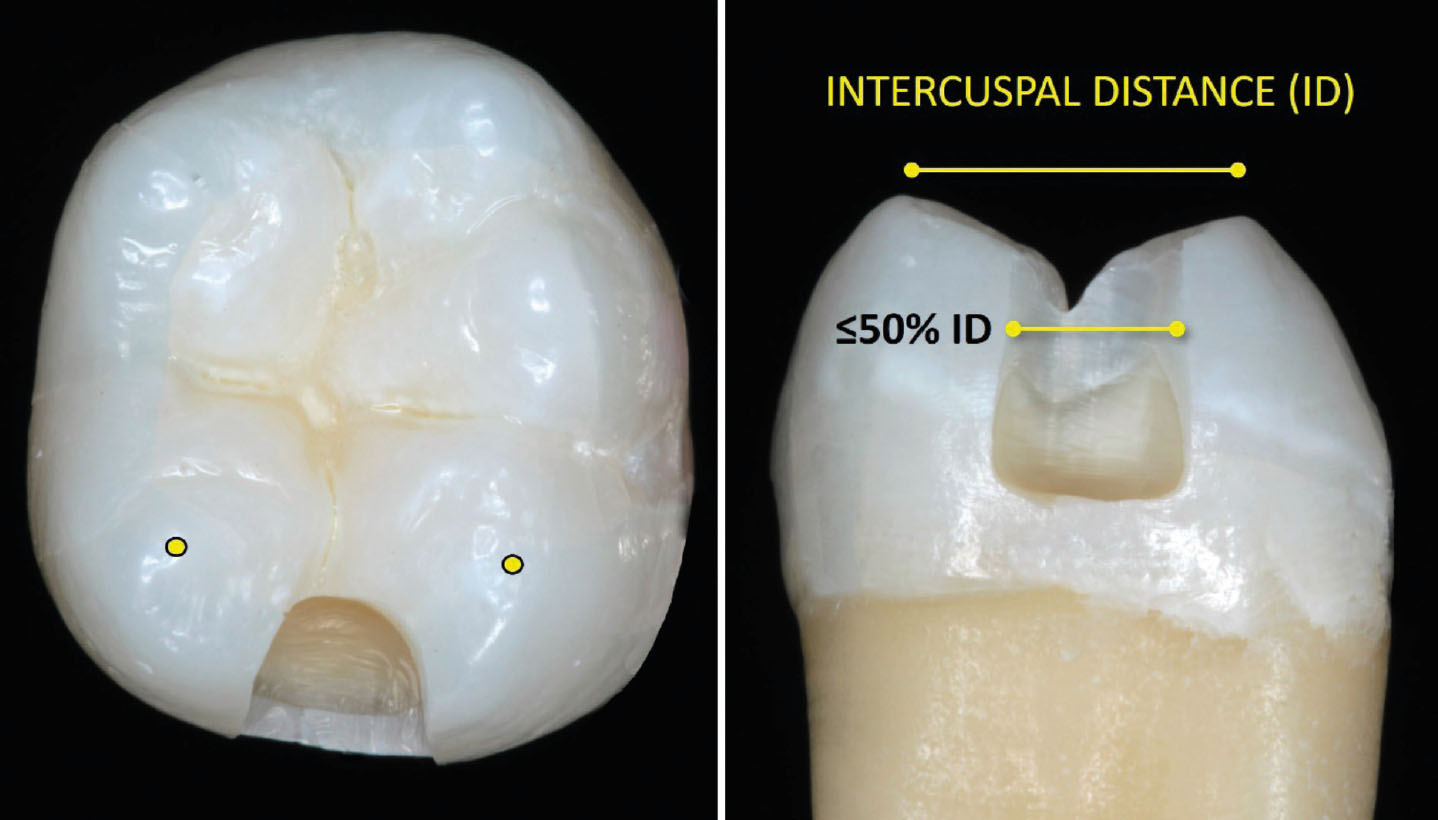

This should have rounded internal cavity line angles. For Class II restorations, the manufacturers of one material, EQUIA Forte (GC, Leuven, Belgium) consider in their product profile3 that a cavity width of one-half the intercuspal width is suitable, with Figure 1 (which has been drawn to scale) illustrating the size of such a cavity: however, a group of researchers (Wafaie et al4) achieved successful results using boxes of one-third the intercuspal width, hence this is recommended. However, in situations where the interproximal box width is greater than recommended in light of current knowledge, patients/clinicians may opt for a contemporary GIC or glass hybrid and accept that the restoration will be less costly and could act as a long-term provisional. Other conditions, such as the occlusion, should be considered.

On the other hand, either of these cavities (ie half intercuspal width, or one-third intercuspal width) may also be considered be suitable for use with a resin composite material.

Restoration placement

First, the manufacturer’s instructions for placement should be read and followed, and then the cavity should be isolated. Cavity conditioner is recommended: this is generally 20% polyacrylic acid and is designed to improve adhesion to tooth substance. If the manufacturer suggests its use, the cavity conditioner should be applied using a cotton pellet or a brush for 10 seconds in order to remove the smear layer. Rinsing is not necessary, with moist cotton pellets being used instead, and it is not necessary to dry with an air syringe, instead use dry cotton pellets.

The restorative materials should be injected into the cavity, starting from the bottom (obviously!) until the material had extended over the marginal ridge. Wafaie et al.4 suggest the use of a gloved index finger (coated with a very thin layer of separation medium, such as Vaseline or cocoa butter) to apply pressure to the material in a so-called ‘pressfinger technique’. This is followed by compaction with a manual instrument to allow maximum adaptation of the material to cavity floor and walls, with a view to avoiding voids and ensuring good adaptation at the cavity floor, walls and internal line angles. There is a ‘window of opportunity’ for placement:

- Too soon = the material sticks to everything;

- Too late = it is not packable.

After the recommended setting time, the matrix (for Class II) should be removed (vide infra), and the restoration shaped and finished using high-speed or medium-speed extra-fine diamond finishing instruments under water coolant, with the proximal surface being finished with flexible discs. Ideally, it has been suggested that finishing is delayed for 24 hours (certainly for older GICs), but the practicality of getting the patient to return for this means that this is not usually feasible. If a resin-based coating is suggested by the manufacturers, it should be applied to the occlusal surface using a microbrush, and the coating passed down the interproximal surface using dental floss and then light-cured for the recommended time.

In that regard, for Ketac Universal Aplicap (3M, St Paul, MN, USA) restorations, there is no need for cavity preconditioning or surface coating, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Matrices

An anatomically contoured matrix, such as a sectional matrix system should be used with a separation ring, but, despite the contour of the matrix, burnishing should be carried out in order to ensure an anatomically correct, tight contact. Circumferential matrices such as SuperMat (Kerr Mfg Co, Orange, CA, USA) are excellent, but will also require burnishing. Wedges are always necessary, because the metal within the Supermat matrix ‘spiral’ stretches, hence the matrix is never absolutely tight.

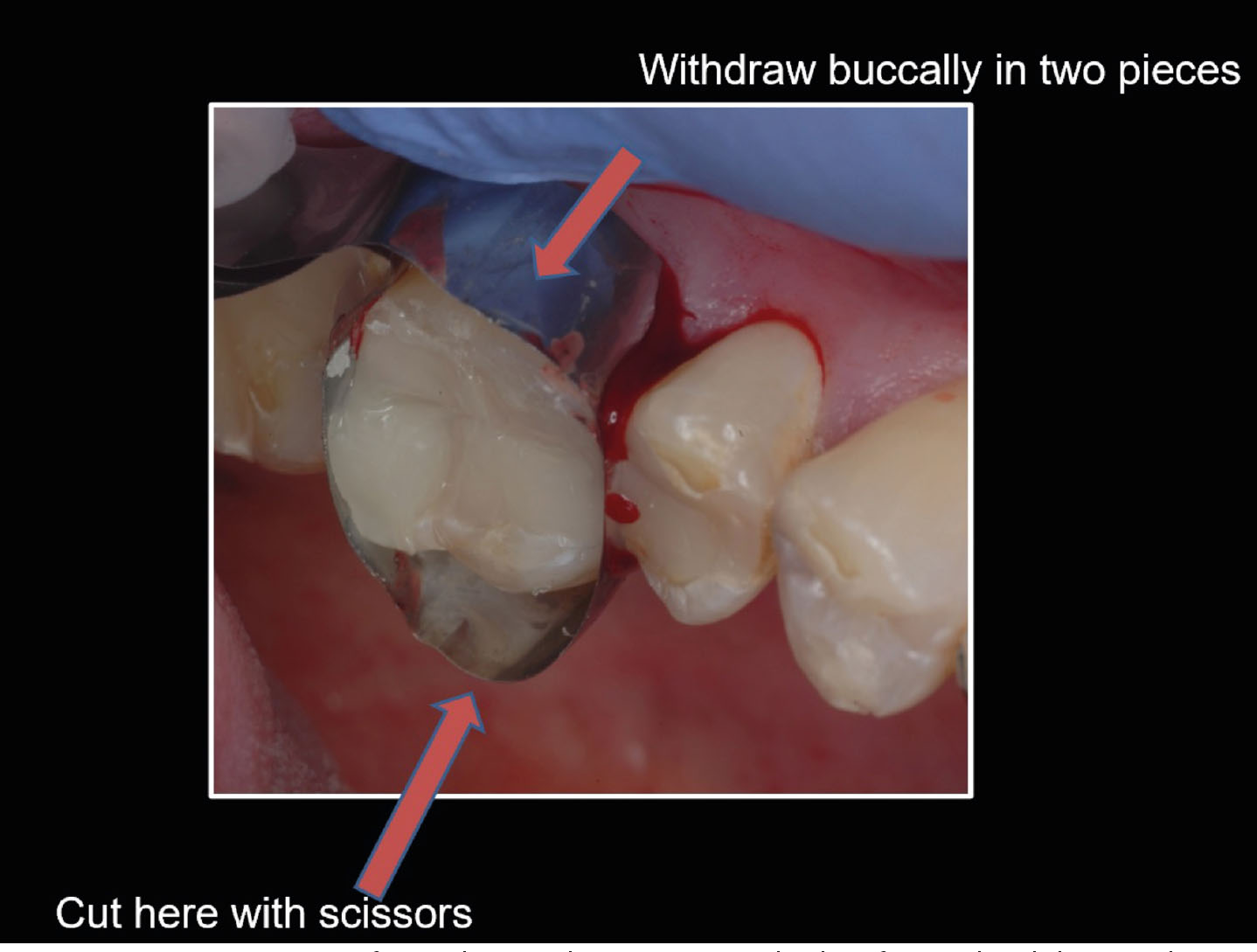

Regarding removal of the matrix, the clinician should not attempt to remove the matrix in an occlusal direction, as this may cause fracture of the setting restoration. Indeed, if it is possible to remove the matrix in an occlusal direction, this is likely to indicate that a tight contact has not been achieved. Therefore, for a circumferential matrix that has achieved a tight contact, it will be necessary to cut the matrix at its palatal aspect with scissors and withdraw the two halves from a buccal direction (Figure 2). Any excess may be easily removed with a sharp sickle scaler, or a scalpel blade.

Glass Ionomer adheres chemically to metal,5 and thus can bond/stick to metal matrices. Therefore, if the matrix is (forcefully) pulled off before the GIC has fully matured, microcracks can form in the proximal surface or result in partial debonding of the material at the bottom of the cavity.

Therefore, a coated matrix should be used, such as those shown in Figure 3, or the matrix coated with a thin film of Vaseline. No attempt should be made to pull the matrix off in an occlusal direction.

The interproximal surface

Some GICs are soluble in dilute organic acids, and therefore can dissolve interproximally in high caries risk cases.6 For materials that comprise a coating as part of their system (eg EQUIA Forte), the coating should be applied to the interproximal surface using floss. Another reason for using an interproximal coating – GICs may react to apple juice and orange juice due to chelating carboxylic acids in the juices. Conversely, the phosphoric acid in cola drinks has no effect!

Occlusal contacts

Frankenberger and colleagues,7 in reviewing the results of their 2-year study, concluded that the presence of an occlusal contact on the interproximal box area of a GIC restoration leads to increased risk of bulk fracture of the restoration and that this was more important than cavity size. They added that the risk of fracture was only for Class II restorations, ‘which have a higher load situation compared to Class I restorations in which the brittle GIC material is always completely surrounded by enamel and dentine’. However, they had a patient drop-out rate of 76% over the 2-year period, and this reference is now 13 years old. This advice may therefore have been made redundant by the use of newer GIC variants, but, nonetheless, until proven otherwise with these newer materials, the present authors suggest avoidance of occlusal contacts on Class II boxes.

Heat cure

Results of one laboratory research project, by Šalinović and colleagues,8 have indicated that the physical properties of one GIC variant (EQUIA Forte) are enhanced by a 30-second heat-cure. Therefore, if your surgery light cure unit (LCU) is of a type that is designed to give off heat at its tip, the present authors suggest thermo-curing by holding the LCU close to the restoration surface for 30 seconds.

WARNING: for Class V restorations, be aware of the possibility of burning the gingival tissue adjacent to the restorations if it is touched by the hot LCU.

Conclusion

Achieving a satisfactory restoration requires the clinician to pay attention to detail at each stage. Placing the latest GICs is no different. Nevertheless, when faced with a patient, restoration and clinical scenario involving restoration of a posterior tooth, there is a choice between (amalgam), resin composite and GIC variants, the clinician has to weigh up the options and decide what material to use.