Article

Oral sarcoidosis of the lip: a case report and lesson of availability bias due to SARS-CoV-2

We highlight the case of a 44-year-old female who presented to the oral and maxillofacial department following an urgent referral and who had an enlarging lesion on her lower lip, present for 7 weeks. History revealed that the patient had a previous laceration to the lower lip when she was aged 5 years, which was closed primarily. She had a secondary complaint of a dry cough, mild shortness of breath and difficulties in accessing primary care due to suspicions of coronavirus.

On examination, there was a 30-mm raised, red, indurating lesion inferior to the midline of the lower lip, below the vermillion border (Figure 1). The lesion involved the inner labial oral mucosa. Application of the surgical sieve for differential diagnoses for this lesion emphasized a need to rule out a neoplastic origin.1 The patient had an incisional biopsy under local anaesthetic of the inner labial mucosa with two samples taken, one superficial and a further deeper sample. Taking a sample intra-orally, reduced the risk of visible scarring.

The histology showed non-caseating sarcoidal granulomata tissue and fragments of refractile and birefringent material, which was likely to be related to the prior injury. It was also noted that a sarcoidal reaction to an identifiable foreign body does not exclude sarcoidosis, and that there was no evidence of malignancy in the sample.

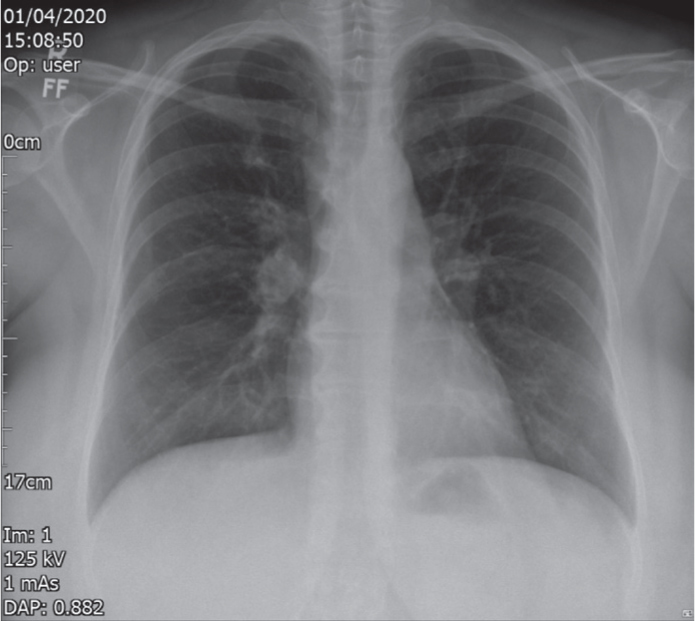

Investigations, which included serum ACE, calcium levels and a chest X-ray, confirmed the pathological signs of sarcoidosis (Figure 2). Following this, the patient's lip lesion was treated with topical steroids (triamcinolone) and she was referred to respiratory medicine. By the 12-month follow up, the lower lip lesion had resolved with minimal scarring and no recurrence.

This case acts as a reminder for clinicians to be aware of coronavirus overshadowing the need to rule out other diagnoses when oral lesions present as the first symptom of a potential systemic disease. Awareness of red flags and surgical sieve guides for differential diagnoses will help clinicians to not misdiagnose due to availability bias and clouding by COVID-19.2

This case used a non-surgical approach, and we therefore minimized potential scarring as shown at the follow up (Figure 3). This could be an aesthetic issue because the lesion was on a prominent facial area. All options should be presented to patients, but it may be preferable to use less invasive options initially before progressing to surgical excision.

This case is unusual as sarcoidosis presenting with oral lesions is particularly rare. In an era of SARS-CoV-2, surgeons and clinicians should be mindful of causes other than coronavirus for shortness of breath and dry cough, when patients also present with oral facial lesions.